When images are life, what can we do with film?

The Situationists were a French group of writers, petty criminals, artists and activists who sought to critique and revolutionise the ‘everyday life’ they found themselves entrenched in during the 1950s and 60s. They published an aggressive journal, wrote pamphlets supporting the May 1968 strike in France, walked about the streets of Paris, and Guy Debord, considered either the corner stone of the group or dictatorial ideologue, made films to criticise the increasing reduction of lived experience to a sequence of images to be consumed.

In opposition to this ‘society of the spectacle’, they desired to construct ‘situations’ which would reveal the subtle forms of control that direct our everyday existence and encourage people to take hold of their own time, live without boredom and without work that was considered exploitative and alienating. The everyday experience is not simply a trivial moment for the Situationists, it is of utmost importance in imagining a new society where we are in charge of our own future, where the imagination is free to create a new world.

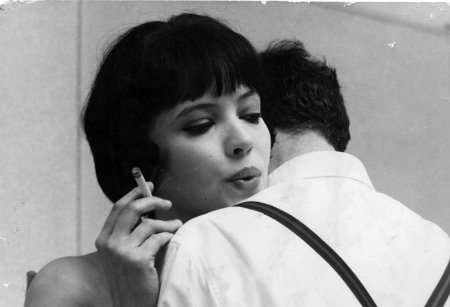

The Situationists sought to critique every aspect of capitalist and socialist society and this included the rising success of Hollywood and left-leaning French New Wave. They violently attacked the films of Jean-Luc Godard that depicted crime and romance by ordinary people in an effort to show the reality of lived experience in the new affluent yet estranged and increasingly commodified Europe. Godard’s project, as understood by Debord, was to show the downtrodden people how they could liberate themselves by watching his films.

According to the Situationists, making films in this manner was a step in the right direction, but in the end would only serve to make people consumers of a new kind of pseudo-critical image of society. Watching Godard’s Tout Va Bien (Everything is Fine), a story of a strike at a factory that attempts to critique the medium of film by including extremely long shots of the workers ransacking offices and youths encouraging people to steal everything possible from a supermarket, the viewer is meant to see the possibility of breaking free of both capitalist society and the conventional passive way in which we watch films. While sitting in the dark cinema we forget our sense of time and place as our attention is directed to the screen where images give us, temporarily, a new construction of reality. Godard hoped that his films would awaken us to the reality of this situation, encouraging us to take hold of our lives and create a new world where we could truly express ourselves, rejecting the attempts by conventional cinema to give us easy to digest images that only function as entertainment, revitalising us only so we can return to work the next day.

Do we simply watch the images rolling past, become happy or sad at the whim of the filmmakers, only to return to our regular lives without any effect on how we view the world and how we could possibly change it?

The Situationists saw this as an inherently ‘idiotic’ goal that would only serve as another image to be consumed. While we watch these revolutionary images, we distance ourselves even more from the possibility of taking hold of our own lives by considering them as entertainment. They virulently attack the idea that by watching films, even one’s portraying struggle and oppression, one can break free of the stranglehold of a society divided into those that create images (Godard, bosses, politicians) and those that consume these images (workers). This idea is captured by the Situationist phrase ‘you can’t fight alienation with alienated means.’ In reference to film, this simply means that you can’t bring change into the world by creating an image of it; real change is not the representation of change, but the end of representation itself. After that we would not seek to consume images of what we think society should be, or what we would ideally like our life to be. Life would be the lived experience of the world we live in with connections to places and events that we make, not one’s given to us by professional politicians or sold to us by filmmakers.

This raises many problems about what films are trying to make us into. Do we simply watch the images rolling past, become happy or sad at the whim of the filmmakers, only to return to our regular lives without any effect on how we view the world and how we could possibly change it? Guy Debord’s films, which he later rejected for reasons that he criticised Godard’s films for, were more like anti-films. At the end of Sur Le Passage De Quelques Personnes À Travers Une Assez Courte Unité Du Temps (On The Passage of A Few Persons Through A Rather Brief Unity of Time) Debord questions whether there was any point to making the film, forcing us to wonder what was the point and, importantly, if this film, as a collection of images that I sat and watched, only reinforced the control of images.

What good does a filmic critique of film do when afterwards I consider it, ponder some little thoughts about the world and then check my e-mails and revert back into anxiety about exams and future employment? I could have been tearing down advertisements, making love instead of going to work, or simply walking through my neighbourhood in a way that it was never designed for. For the Situationists these simple acts can be rupturing events that cannot be incorporated into the regular sequence of images that we are fed. We should wonder how films work on us and what can we do with an image that doesn’t placate or simply give us a little break from the anxieties of our lives?

(Header Image Source, Image 1, Image 2, Image 3)

Comments