White Cargo: a history of the slave trade in black and white

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he slave trade: a staple part of your History education at school. The phrase conjures up images of malnourished Africans in disease-ridden slave ships, intensely labouring on sweltering plantations, or being whipped and branded by sadistic European owners. And of course, this insight is buttressed by the recent award-winning films Django Unchained (2012) and 12 Years A Slave (2013).

But did you know that a white slave trade preceded the black?

As a History undergrad reading White Cargo by Don Jordan and Michael Walsh, I was shocked by the extent of airbrushing that my education has undergone. Although early modern history usually sends me to sleep, I was hooked. It turns out that, from the late sixteenth to early eighteenth century, the white ‘dregs’ of British society were sent over to America and the West Indies to cater for the tar making, gold mining, cash crop and pearl-diving ventures. Even George Washington, the first president of the United States, owned white slaves.

As a History undergrad reading White Cargo by Don Jordan and Michael Walsh, I was shocked by the extent of airbrushing that my education has undergone. Although early modern history usually sends me to sleep, I was hooked. It turns out that, from the late sixteenth to early eighteenth century, the white ‘dregs’ of British society were sent over to America and the West Indies to cater for the tar making, gold mining, cash crop and pearl-diving ventures. Even George Washington, the first president of the United States, owned white slaves.

In this slave trade, the rights to an individual’s labour for a set number of years (usually seven) was exchanged for their fare across the Atlantic from Britain, as well as a reasonable amount of land to use at the end of their contract. Oftentimes this promise was never fully adhered to, and it was commonplace for the white ‘servants’ (simply a synonym for slave) to die before they found out. The scheme not only removed the poor and worthless from England, but allowed convicts to be sent away as punishment to reduce crime rates and avoid overflowing prisons. Additionally, as it was thought that children’s bodies could acclimatise to the heat of the New World more easily, a business in kidnapping children blossomed. Kids were even court ordered to carry out an ‘apprenticeship’ abroad despite parental protests.

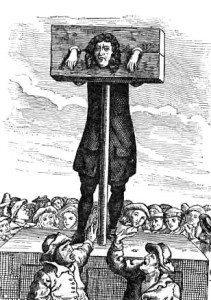

The treatment of white slaves abroad was appalling. For example, some travelling ‘servants’ died from dehydration (despite a plentiful supply of water on board) so that the captain could save on expenses. Female slaves who had been raped by their masters had to serve the compulsory extra two years if they bore a child. Food was limited and the work hours were inhumane, much like the conditions faced in the later stages of the slave trade by Africans. Moreover, brutal punishments were dished out: we are told of one slave that was ordered to the pillory for four whole days, and received a public whipping on each day as his ears were nailed the posts.

Many slaves were even prepared to run away from their callous owners and tough it out with the Native Americans, who had a vicious reputation among the European trespassers.

Interestingly, the University of Warwick’s local area also features in this book. It is reported that 2,000 beggars roamed the streets of Coventry in 1570, which probably benefitted from their removal to the new American colonies, or the commercial lands of the West Indies. Furthermore, not only did the Earl of Warwick prosper from the white slave trade on his estate in Somers Islands (labelled as Virginia’s sister colony), but also the first African slaves were traded on his territory in 1619.

Yet the major bombshell was the level of intolerance that those from Ireland encountered during this time. The dehumanisation of the Irish echoes the fact that colour was not an automatic factor used to pinpoint one’s position in the social hierarchy. A disproportionate majority of white servants deported to Virginia, Maryland and Barbados (the three key areas analysed in the book) were from Ireland: this supplied free labour and released Irish land for aspiring English planters during the Cromwellian era.

Yet the major bombshell was the level of intolerance that those from Ireland encountered during this time. The dehumanisation of the Irish echoes the fact that colour was not an automatic factor used to pinpoint one’s position in the social hierarchy. A disproportionate majority of white servants deported to Virginia, Maryland and Barbados (the three key areas analysed in the book) were from Ireland: this supplied free labour and released Irish land for aspiring English planters during the Cromwellian era.

The English saw the Irish as savages and vermin that needed to be ousted; therefore certain laws, we learn, pardoned English murderers if they could prove that their victim was Irish. The prejudice did not stop here. The Irish Catholics who were sold off as slaves and faced terrible living and working conditions – simply due to their ethnicity and religion – even found themselves banned from the Catholic services in the French and Spanish settlements. They were clearly seen as the inferior whites.

To really put their position into perspective, Europeans were so suspicious of the Irish that, in the 1690s, African slaves were trusted to form a militia to put down their rebellions.

[pullquote style=”left” quote=”dark”]Is it fair for historical discrimination against the Irish to be swept under the rug whilst events like Black History Month are celebrated?[/pullquote] There has been an overwhelming focus on the historically racist attitudes towards Africans in the past in an attempt to right Europe’s wrongs. It is true that Westerners were indentured for a certain period of time, whilst Africans were – more recently – enslaved for life. However, like Africans, the Irish not only experienced prominent racism up until the last century, but scientific attempts (by measuring skull sizes) were also made to prove their inferiority to other Europeans. We now know that they were also heavily used as slaves.

Whilst the relationship between black and white people charts a crucial and positive change in the history of mankind, context is always essential. Consequently, I believe that all students should be taught the horrors of the prior white transatlantic slave trade as part of their basic historical knowledge too.

Thought provoking and an eye-opener of a read, I would definitely recommend White Cargo for anyone with an interest in early modern history, slavery, British imperialism and the establishment of North America.

Comments