Gender and genre: the politics of pseudonyms

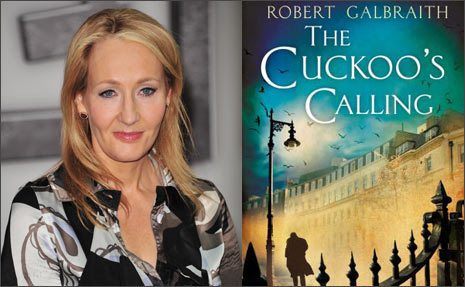

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]ith JK Rowling’s second crime novel, The Silkworm, due to hit the shelves next month under the leaked pseudonym of Robert Galbraith, one can’t help but speculate about the motives of such well-known authors in masking their identities.

In the case of Rowling, these have been made plain upon the media’s inquest – ‘to work without hype or expectation and to receive totally unvarnished feedback’ from publishers, reviewers and readers. If her intention of distancing herself from the much-celebrated Harry Potter series is true, this certainly remains amongst the most noble of reasons for anonymity. To allegations of a cynical marketing ploy, Rowling’s common retort is to reiterate the novel’s success prior to the disclosure of its true authorship. Robert Galbraith’s accomplishments were on a par with that of JK Rowling at the equivalent stage in her writing career.

To skeptics’ further queries surrounding the decision to adopt a specifically masculine alias, Rowling insists that it simply makes manifest her desire to inhabit a persona as far removed from her reality as possible.

The prejudicial question of gender in matters of authorship remains a very real one. Although the hardship suffered by female writers remains a far cry from that faced by the Brontë sisters, for instance (who published under the names Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell out of pure necessity) women are often compelled to adopt male alter-egos in the interests of publication and sales. After all, Rowling’s choice to publish under her initials was not merely an arbitrary one.

The prejudicial question of gender in matters of authorship remains a very real one. Although the hardship suffered by female writers remains a far cry from that faced by the Brontë sisters, for instance (who published under the names Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell out of pure necessity) women are often compelled to adopt male alter-egos in the interests of publication and sales. After all, Rowling’s choice to publish under her initials was not merely an arbitrary one.

Even in terms of genre, gender-based assumptions remain rife, with romance erroneously perceived as the domain of female authors and crime writing as dominated by men. Beneath the surface-level admiration from Rowling’s own editor, his words are liable in perpetuating such prejudices. His statement that he ‘never would have thought a woman wrote [The Cuckoo’s Calling]’.

The decision of well-known authors to adopt a nom de plume, however, often extends beyond the question of gender or, indeed, genre. Stephen King’s decision to operate under a pseudonym, Richard Bachman, was simply a pragmatic measure intended to maximise his rate of production; early in his career, he claims, ‘there was a feeling in the publishing business that one book a year was all the public would accept.’

[pullquote style=”left” quote=”dark”]The continuing necessity for pseudonyms indicates a worrying prejudicial side to the publishing industry. [/pullquote] The motivations behind the use of pen names amongst writers are diverse. Where the said author does so with the purpose of inviting fresh and unfettered feedback, however, the venture is certainly a brave one. As long as these ventures do not detract from the discussion of the actual writing, as was such with JK Rowling’s pseudonym where the fallout resembled a ‘whodunnit’ itself, they should be wholeheartedly encouraged by the literary community.

Comments