Celeste: a Graphic Novel with a Timely Twist

[dropcap]H[/dropcap]ow would you react if you found yourself suddenly alone in the world? Would you search for your loved ones? Break the law? Carry on walking as if nothing had happened? This is the dilemma faced by three groups of characters in I. N. J. Culbard’s new graphic novel, Celeste, when their ordinary lives are interrupted with the sudden disappearance of everyone around them.

[pullquote style=”left” quote=”dark”]It is a tale of cosmic proportions.[/pullquote]The book starts far from the Milky Way, showing the star-flecked universe in all of its impersonal vastness. As our view zooms in on three everyday scenes, passing gorgeously rendered planets and stars, we meet our characters. Lilly is commuting to work on the London underground, trying to ignore the whispered remarks from fellow passengers about her albinism, when she locks eyes with a woman named Aaron; Ray is driving on the 405 Freeway when he gets a phone call from the LAPD concerning his wife; and Yoshi is preparing himself for death in the Aokigahara Forest when a voice shouts for him to stop. Then everybody else disappears, and three separate stories unfold. This may be Culbard’s first original graphic novel, but there is no beginner’s hesitation apparent in its ambitious story and stunning artwork.

Celeste is a powerful, bold debut that will leave readers puzzling long after they’ve turned the final page. Part of the book’s intrigue lies in the trifold nature of its plot. With three sets of characters, spanning a diverse range of locations, it would be easy to assume that the three stories are disconnected – one might even ask why they are contained within the same graphic novel at all. However, Culbard links them together with the most careful precision, cutting each into equal chunks and weaving the story threads together.

Celeste is a powerful, bold debut that will leave readers puzzling long after they’ve turned the final page. Part of the book’s intrigue lies in the trifold nature of its plot. With three sets of characters, spanning a diverse range of locations, it would be easy to assume that the three stories are disconnected – one might even ask why they are contained within the same graphic novel at all. However, Culbard links them together with the most careful precision, cutting each into equal chunks and weaving the story threads together.

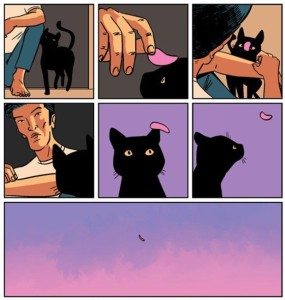

The characters’ actions mirror one another, creating the impression of a causal connection between them all. The theme of fate is prevalent in Culbard’s narrative, communicated through the leitmotifs of a pink flower petal that visits each story, and the ever-watching, impassive moon. The implications of these connections are left without explanation: are the characters governed by destiny? Has some deity intervened? Is this the bizarre prank of a playful alien? Perhaps the parallelism of events is down to nothing more than coincidence.

Another effect of this parallelism is that Culbard can play with the reader’s expectations. One moment when this is most effective is in a sequence of pages following the disappearance: in the first section, Lilly and Aaron introduce themselves to one another; in the next, Ray discovers a man concealed in the boot of a car; by the final section, the reader is expecting Yoshi’s encounter with an old man on the road. However, Culbard immediately defies that expectation as the man undergoes a disturbing transformation into some kind of monster. With Celeste, one can never be certain of what will come next.

Due to the ambiguous involvement of fate and extra-terrestrial life, the book has been billed by its publishers, SelfMadeHero, as a piece of science-fiction. However, upon reading it, Celeste noticeably spans an amalgamation of genres. This is no surprise given Culbard’s previous body of work: the influence of his graphic novel adaptations of H. P. Lovecraft’s writing is obvious in the grotesque spirit-monsters with which he peoples the Aokigahara Forest, and the murder-mystery of his work with Sherlock Holmes novels seeps into Ray’s search for his missing wife. Culbard even manages to sculpt a convincing romance plot in the story of Lilly and Aaron, which is somehow touching regardless of the unnerving backdrop. Above all these qualities, what really permeates the book is the fluid, surreal sensation of a dream. The bizarre becomes ordinary. In such an unfamiliar world, questioning anything is without purpose, and both the characters and the reader are better off suspending their disbelief.

Despite this surrealism, Celeste still manages to speak to the reader on a real human level. The characters are made believably concrete by tiny details, like Yuki’s handling of his cat, or when Lilly hits the snooze setting on her alarm. It is amazing, in fact, how quickly Culbard can build an impression of each character’s personality through his artwork. A panel of Lilly concealing her albinism with sunglasses manages to convey simultaneously her defiance, her self-consciousness, and her feeling of loneliness. These characters are relatable, realistic people; it is only the world around them which becomes unfamiliar to the reader.

Despite this surrealism, Celeste still manages to speak to the reader on a real human level. The characters are made believably concrete by tiny details, like Yuki’s handling of his cat, or when Lilly hits the snooze setting on her alarm. It is amazing, in fact, how quickly Culbard can build an impression of each character’s personality through his artwork. A panel of Lilly concealing her albinism with sunglasses manages to convey simultaneously her defiance, her self-consciousness, and her feeling of loneliness. These characters are relatable, realistic people; it is only the world around them which becomes unfamiliar to the reader.

In addition to the power of Culbard’s artwork, what impresses me is its maintained brilliance throughout the novel: the quality never deteriorates, nor do the images take a backseat as the plot progresses. Culbard’s use of colour is particularly breath-taking – his frequent employment of complementary pairs to separate background and foreground draws the eye expertly around the page, creating a reading experience that feels intentionally directed.

My favourite colour palettes occur in scenes in the Aokigahara Forest, where the neutral green scenery makes the strange, brightly-coloured spirits burst from the page. Moreover, the sudden tonal leaps of the artistic content is a delight to behold. A vivid double-page spread of rampaging Oni can be followed immediately by a tranquil scene between lovers; an image of two men walking on a sunny day gives way to a grotesque pit of skulls.

It is a mixture of this beautiful artwork and the captivating tension of Culbard’s plotlines that ensure success for Celeste. This is one of those novels that have the power to transport you into another world, which force you to ask the big questions, and which never supply answers. Although the enigma of the book may be off-putting for some readers, for me it is what makes Celeste worth reading.

Comments