Sue Townsend: a writer who captured what it means to be young

[dropcap]S[/dropcap]ue Townsend never had it particularly easy for most of her life. In fact, that is an understatement; for most of it she was extremely poor. In that bleak backdrop, the moments of hilarity she extracted from the life of the hapless Adrian Mole are made even brighter.

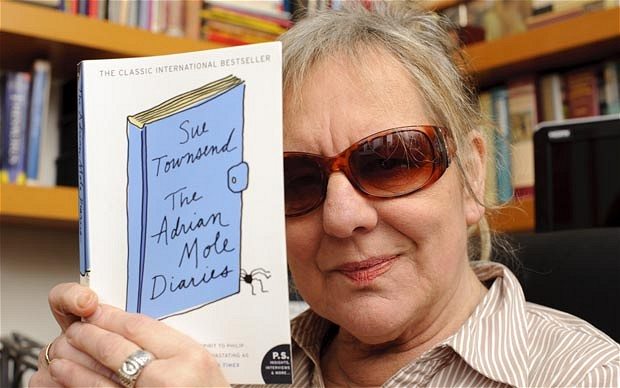

Born in 1946 in Leicester into a working-class background, Townsend’s parents laboured in a series of menial jobs. Plagued by ill-health her entire life, Townsend contracted mumps at the age of eight, and it was while bed-bound by the disease that she discovered her love of reading through Richmal Crompton’s Just William series. She failed her 11-Plus (a damning indictment of that system if one was needed) and she went to a secondary modern, leaving at the age of fifteen. By 23, she was divorced with five small children, and found herself in considerable poverty. She once had to feed herself and her children on a tin of peas and an Oxo cube. Though she would later become comfortable through the sales of her books, she would never forget these extremely lean years, and the social conscience of her work cannot be stressed strongly enough, given the return to 1980s-style poverty many people are experiencing now.

[pullquote style=”left” quote=”dark”]Adrian Mole is a character for the ages.[/pullquote]

A hopelessly awkward, pretentious teenage boy of 13 3/4, he struggles with being ‘an intellectual who is not very bright’ and his infatuation with the hopelessly out-of-his league Pandora. Mole’s total confusion as to what he is supposed to do and how he is supposed to act around the object of his affections, his terrible attempts at poetry (‘Pandora! / I adore ya! / I implore ye / Don’t ignore me’) and his occasional sessions in the bathroom with a ruler are a razor-sharp insight into the mind of a young man, made even more remarkable by the fact they were written by a woman.

A lifelong socialist, Townsend’s political convictions permeated her work. A forgotten subplot of the early Mole novels is the family’s struggle to make ends meet, and later the nouveau-riche Pandora becomes a New Labour MP, hardly a development Townsend would have welcomed (although she couldn’t make Pandora vote for the disastrous Iraq War). A later novel, The Queen and I (1992) imagines a republican government making the Royal Family live on a council estate, an apt and wry idea that many can sympathise with in a country even more unequal than in Townsend’s ’80s heyday.

A lifelong socialist, Townsend’s political convictions permeated her work. A forgotten subplot of the early Mole novels is the family’s struggle to make ends meet, and later the nouveau-riche Pandora becomes a New Labour MP, hardly a development Townsend would have welcomed (although she couldn’t make Pandora vote for the disastrous Iraq War). A later novel, The Queen and I (1992) imagines a republican government making the Royal Family live on a council estate, an apt and wry idea that many can sympathise with in a country even more unequal than in Townsend’s ’80s heyday.

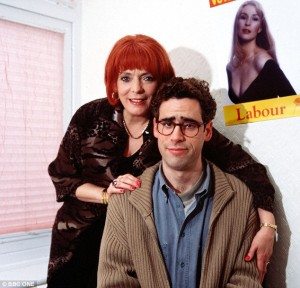

Townsend was also a distinguished playwright and the ’80s saw her cover agoraphobia, illiteracy and the lives of women in Leicester’s sizeable Asian community on the stage. But again, it was Mole that saw her biggest success: the first novel, adapted for theatre, ran for two years in London.

She was beset by health problems her entire life, and over the years suffered from peritonitis, diabetes, arthritis and kidney failure, and went blind towards the end of her life, ending up dictating her books to her son to type out. She was writing a new Adrian Mole book when she died, and it is a shame we will not get to hear what Adrian will be up to next in the life she gave to her most celebrated character.

What’s the point of art? Far from it being useless in the Wildean maxim, the best art says something fundamental about us and our society. Sue Townsend’s best work chronicles both the brutal, baffling world of the 1980s transformation and the timeless awkwardness of adolescence. Many writers manage to talk about either the political situation of their day or the human condition. Sue Townsend did both with consummate skill and of course, a great sense of humour.

Despite the books being distinctly British, they have been translated into 48 different languages and sold millions of copies worldwide. Perhaps this tale of struggle and confusion is more timeless than it seems. This can perhaps be attributed to Townsend putting so much of herself into her work. Her poor health was reflected in Adrian’s cancer and his friend Nigel’s blindness, an affliction Townsend herself found particularly upsetting. Her last novel was called The Woman Who Went to Bed for a Year (2012) and in the end, beset by disease, that is what Townsend had to do.

Sue Townsend leaves behind her a husband, four children and ten grandchildren. But she leaves a lot aside that, too: a body of work that showed she really understood what it was like to be young, poor and disadvantaged. All this was embodied in one character, a surrogate son through which to tell the story.

Comments