Laver it or hate it: Can we predict fashion?

Chloe Wynne puts James Laver’s theory to the test.

Fashion is perhaps one of those areas where you may not expect grand theories and theses to emerge. We all have our ideas of what’s hot and what’s not, but surely this can’t be condensed into one theory fit for everyone’s taste, can it?

One guy though, art historian and museum curator James Laver came up with his own law in an attempt to outline our opinions on styles gone by. His idea is focused around time and how our idea of what is a good look depends on how far away the style is from the current day. So, he would find the typical 80s gear of shoulder padded power suits amusing, not because of its bold features, but rather because it was around on the fashion scene 30 years ago. His theory ascribes such adjectives as amusing to time periods ranging from ten years in the future to over a century and a half in the past, as shown in this table:

|

Indecent |

10 years before its time |

|

Shameless |

5 years before its time |

|

Daring |

1 year before its time |

|

Smart |

Current fashion |

|

Dowdy |

1 year after its time |

|

Hideous |

10 years after its time |

|

Ridiculous |

20 years after its time |

|

Amusing |

30 years after its time |

|

Quaint |

50 years after its time |

|

Charming |

70 years after its time |

|

Romantic |

100 years after its time |

|

Beautiful |

150 years after its time |

Surely though, what is ‘in’ and what isn’t, is all down to our own individual styles and tastes? Laver would agree – in an unexpected way. For him, style is focused around the erogenous zone of a particular era. So, if we as a society lap all the attention onto breasts in one decade and then our legs the next, fashion will pursue such a change and adapt to suit it. In the 1920s when luscious, long legs were all the rage, for example, the designers of the time produced some pretty cute novelty stockings to accommodate it. Yet only a few years later the erogenous zone had switched to the back, and so in came the sleek dresses of the 30s.

When first setting eyes on this grand thesis I was admittedly intrigued and soon got hooked into hunting through online archives at a range of collections in the past 150 years to see if my opinion was, as Laver would expect, more relative to my place in time than my taste. At first, I thought the old chap had done wonders and really managed to condense taste into one simple law. However, when testing his theory on other people in a mini-survey, it seemed to be quashed fairly easily.

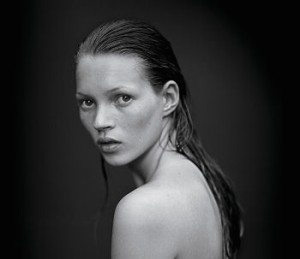

The first look put to the test was the 1990s ‘heroin chic’ look, as forwarded by Kate Moss and friends with her sunken eyes, hollow face, and depressive allure. I have to agree with Laver on this one and would say that 20 years after its trendiness, heroin chic is now ridiculous. However, over 25% of those who participated in my survey described the look as beautiful. It’s beyond me, but each to their own. In James Laver’s Law ‘beautiful’ should be the word used for outfits from 150 years ago rather than 20, so the first test of the day seemed to really negate Laver’s proposal.

It was also interesting to see gender play a role in this little quiz, with more men than women seeing Moss’ drugged up gaze as ‘beautiful’ than women. Women generally opted for ‘romantic’ or ‘hideous’, two terms so opposing that you have to wonder just how much personal taste plays a part over time in our opinions of style.

Time is important – just not in the way that Laver suggested. The older generation of participants regarded heroin chic as ‘hideous’ whilst the under-21s preferred again to see it as ‘beautiful’. The 1860s dress that should have been awarded the term ‘beautiful’, on the other hand, was instead seen as ‘quaint’ or ‘dowdy’ – again showing just how polarised taste can be. What seems to be coming through here is that style is subjective, and not fixed into one set model, which seems to be stating the obvious.

The final two tests proved no different in working against Laver’s Law – a pretty OTT piece from the 80s was backed as ‘hideous’ when the theory would have instead ascribed the adjective ‘amusing’. Nevertheless, an age gap was noted again with all of the over 50s quizzed seeing it as Laver would: a bit of a laugh. Finally, the hobble skirted dress typical of the 1910s was looked on as ‘ridiculous’ by the majority of those surveyed rather than its prescribed term ‘romantic’.

Of course, there are holes in Laver’s Law. Perceptions of what is stylish and what is an absolute flop rely more on our own visions than our point in history. However, these two are related; our ideas of style are ultimately products of the world around us and what is deemed acceptable to wear. And so, when related specifically to erogenous zones I feel that James Laver was on target with his grand idea. If in 2024 the freshers of Warwick are really keen to show off and accentuate their …elbows (silly example, I know) then a piece of clothing being released now that fulfils that trend perfectly would most likely be seen as indecent. The same idea would be applicable to how people of the 1950s would have reacted to the mini-skirts of the following decade.

Laver’s theory is really more to do with sex appeal than taste, and with all the different adjectives you still hear now floating around to describe that girl’s dress in Neon, or another girl’s top in Moo Bar, I don’t think we should be quick to dismiss Laver’s approach, and the significance of the erogenous zone in shaping our opinions on fashion.

Comments