122 Years of Walt Whitman

[dropcap]T[/dropcap] he 26th of March marked the 122 year passing of the poet Walt Whitman. This gives us a good excuse to stop and consider his work, because he was one of the greatest poets who ever lived, as well as a really friendly guy.

[divider]

I celebrate myself,

And what I assume you shall assume

For every atom belonging to me as good as belongs to you. (‘Song of Myself’, 1-3.)

[divider]

‘Song of Myself’ is the name of his most seminal poem; a sprawling work of genius which begins his world-famous collection, Leaves of Grass, first published in 1855. And as openings go, they don’t get much chummier than this. In the first line, Whitman declares that the topic of his poem is ‘myself’. But this isn’t as arrogant as you might fear, for everything of ‘myself’, ‘as good belongs to you’. Whitman, therefore, wants to celebrate everyone and everything. What an old softie.

Whitman’s subject matter, for the period in which he was writing in, was more or less unique. And indeed, most aspects of Leaves of Grass can be described as unique. Form-wise, for example, Whitman wanted to be read by as many people as possible. So he decided to write in free verse, a poetic technique relatively unknown in Whitman’s native America at this time (this does away with all of those boring metre patterns you probably had to learn at GCSE). Within his free verse, Whitman wrote about awesome things such as the universal equality of all the peoples of the world, the sanctity of nature, and the joys of sexual experience. It was just a bit of a bummer that the vast majority of the American populace didn’t really dig equality, nature, or liberal amounts of sex at this point in time.

Unsurprisingly, then, Leaves of Grass caused some pretty big waves in the literary world, and initial reaction to it wasn’t great. In a way its publication was kind of like a literary, nineteenth-century equivalent to the release of The Human Centipede. People thought it was sexually explicit (“obscene literature”), gross (“a mass of stupid filth”), and downright weird (“the book cannot attain to any very wide influence”). However, unlike The Human Centipede, Leaves of Grass also won some influential fans. Ralph Waldo Emerson was mesmerized, and a few decades later every university students’ favourite poet (Allen Ginsberg) fell in love with the poem, and its free verse influence can immediately be detected in Howl.

Ginsberg loved Leaves of Grass because he found it was still relevant in the mid twentieth-century, and his howl of protest was in part so vivid because of his frustration that Whitman’s ideals had not yet been realised. Its heavily idealistic message of peace and tolerance means that its relevance has in no way dissipated in time.

[divider]

This is the grass that grows wherever the land is and the water is,

This is the common air that bathes the globe. (‘Song of Myself, 358-359.)

[divider]

If you’re somehow in any form of doubt as to how that kind of message isn’t especially relevant in 2014, then just pick up any newspaper from CostCutter (get The Sun whilst you still can…) to see headlines on the Ukrainian crisis, or more Taliban attacks in Afghanistan, or the appalling sectarian violence in the Central African Republic, and reconsider. We, in the modern age, have still failed to fully comprehend the ‘common air’ of our shared ‘globe’.

Whitman is therefore still relevant on a very broad level, but more specifically, he’s also exceptionally relevant to us students in 2014. For example, towards the very end of ‘Song of Myself’, in one of the ultimate moments of literary sass, Walt declares:

[divider]

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then … I contradict myself;

I am large … I contain multitudes. (‘Song of Myself’, 1314-1316).

[divider]

As a twenty or twenty-one year old or whatever, everybody is still finding themselves, and Whitman basically here tells us not to pigeon-hole ourselves or to stick too rigidly to a character or persona we adopt. His message is to do what you want, whatever makes you happy, regardless of what people expect or demand from you. You haven’t joined in with the LARP society at Warwick because you worry your housemates will stop thinking you’re that sophisticated, trendy mature student? Sod ’em; if he was here Whitman would definitely be out in a field somewhere with you, happily slaying computer science students dressed up as wizards.

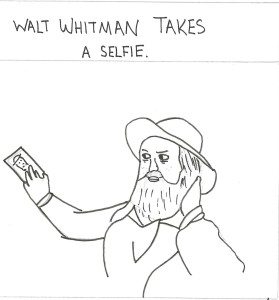

Drawn by Luke Brown

In fact, you can take pretty much any aspect of student culture and there’ll be some part of Leaves of Grass that will immediately become relevant. How about the #nomakeupselfie? Whitman would absolutely love it. If you’re a big fan of the trend then a line such as this one, “Behold I do not give lectures or a little charity,/ What I give I give out of myself” (991-992), will be of particular interest. That’s because the old man urges not to just give charity in a disembodied sense, because it will always remain a “little charity” – instead he urges you to give a part of yourself, too.

If, however, you’re an old-before-your-time pessimistic man like me, you’ll be more than a little suspicious of the need to attach a ‘like’ begging selfie to a supposedly selfless act, and will probably be more interested in the fact that Whitman was a relentless self-publicist (read: attention whore), who made a habit of reviewing his own books, even going as far as to laud himself as “the begetter of a new offspring out of literature”.

Of course, the real reason for Whitman’s relevance to students in 2014 is the same reason for his relevance to anybody else who can read, as well as those who can’t. Because, “Every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you”. Whitman is the universal poet, who wrote for everybody. Forget Disney and Walter White, Whitman has to be the most popular Walt around. If you get a chance this holiday, pick up a copy of Leaves of Grass, a full 122 years after the writer of it died, and see for yourself why the collection is still so needed and relevant. The main piece of the collection, ‘Song of Myself’, ends with Whitman stopping further ahead on the road than us, “waiting” for us to catch him up. He’s still waiting. And that’s why you need to read a copy.

Comments