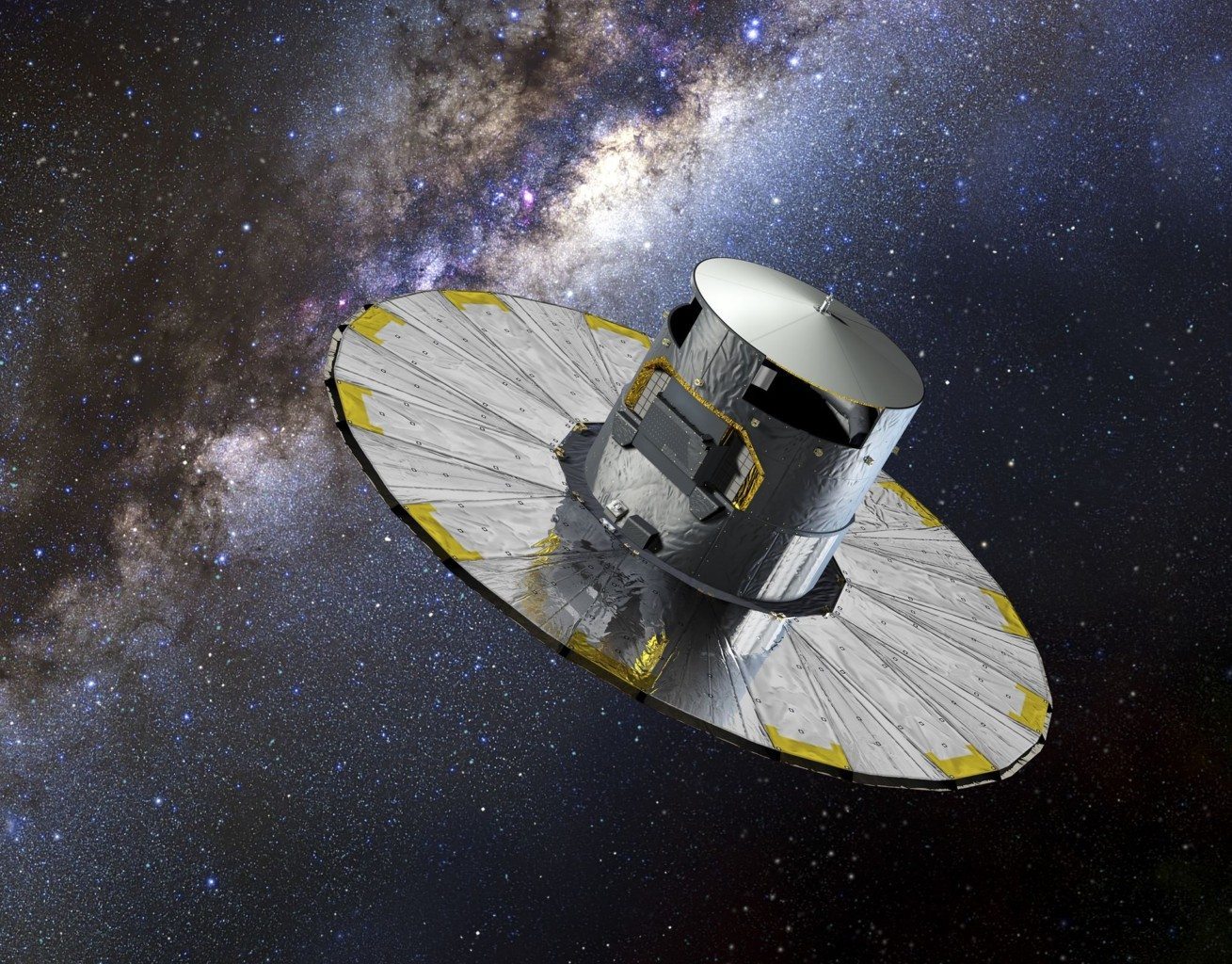

One satellite to map them all

Last month, the European Space Agency launched its newest satellite, Gaia. Gaia’s mission is to record the positions and velocities of approximately one billion stars in our galaxy. At the end of its five-year mission, the mission will have created the most accurate 3D map of the Milky Way ever.

The spacecraft was launched on December 19 from the European spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana and is now on the last stages of its month-long journey to L2. L2 or, technically, the Sun-Earth’s second Lagrange point is a special area in space where an object can orbit the Sun in sync with the Earth without having to orbit the Earth itself. This makes it a popular region to place deep-space telescopes since the Earth will always be between the satellite and the Sun, reducing the amount of solar glare.

Less glare allows Gaia to use its billion-pixel camera to its fullest and detect stars a hundred thousand times fainter than what our eyes can see. Gaia will observe all of the billion stars 70 times, on average, over the mission’s lifetime.

In addition to their positions and speeds, Gaia will also measure other key properties of each star, such as brightness, temperature and chemical composition. Gaia will measure stellar distance through a technique called parallax. Just like both our eyes see things from a slightly different perspective, so will Gaia. As it orbits the Sun alongside the Earth, Gaia will see an apparent change in the position of the stars, compared to more distant objects. With that information and a bit of trigonometry, scientists can measure the distance between us and the star. Accurate parallax measurement, besides helping map our Galaxy, is of importance because most methods for measuring distances outside of the Milky Way depend on it.

But stars are not the only thing that will catch Gaia’s eye. Astronomers are hoping to use it to detect other objects, from asteroids in our Solar System to quasars in the most distant galaxies. By the end of the mission Gaia will have gathered around 1000 Terabytes of data, the equivalent of over 200 thousand DVD’s.

The Hipparcos mission, Gaia’s predecessor, was launched in 1989 and at the end of its four-year mission it had catalogued over a hundred thousand stars. Gaia will be able to catalogue 10 times that amount, to a precision 40 times that of Hipparcos. Although a billion stars sounds like a lot, it is only 1 percent of the estimated number of stars in the Galaxy.

Researchers hope to use Gaia’s data to learn more about the origins and history of the Milky Way and what its future might look like. Like Hipparcos, the data from Gaia is expected to keep astronomers busy for at least a decade.

Comments