Disney heats up its frozen formula

Is Disney’s new movie, Frozen, the most feminist film the studio has ever produced? Although the film has the standard flaws that have bedevilled most of the House of Mouse’s princess films, the story and messages behind the film are a marked and powerful change from almost every other film that is marketed primarily at the young female audience.

Let’s face it: it’s probably the best film since the Disney Renaissance, with a cast that consists of actual Broadway musical performers, making the songs infinitely better. See Tangled for an example of how not to cast a musical, where Donna Murphy is lost amongst the pitiful vocal talent that surrounds her. As a long-time Disney and theatre fan, it’s refreshing to see a cast line-up pulled from Broadway faces, which only adds to the spectacular theatrics of the animation. As Todd McCarthy puts it, “you can practically see the Broadway musical Frozen is destined to become”. The script is genuinely funny, with Olaf the snowman stealing each and every scene he features in.

the core of the film presents a definite “sisters doing it for themselves” impression

But it’s the message which is the most powerful. At the heart of the film, there are two important points made. The first point is all about familial love, especially the love between siblings. As is so often the case in these films, an act of true love is required in order to keep Anna, the film’s heroine, from dying. Although the film seems to progress toward the standard ending, presenting two possible candidates for Anna, it is Anna herself who provides this act of true love, sacrificing herself in order to protect Elsa.

In doing so, she also shows Elsa how to return the kingdom to its rightful state. Essentially, it’s the first Disney film to see the bond of family affect a happy ending, with the romantic interest not even fully resolved by the end, a bold move for a franchise which relies heavily on romantic love and the weight that women should place on finding their “happily ever after”. Disney also shakes up the formula with the characterisation of Prince Hans, and it’s his character that helps to make the second point.

Prince Hans is possibly the worst Prince ever produced by Disney, with the exception of Prince John in Robin Hood (also a villain). A character that is cleverly portrayed to make us root for him until he betrays Anna, a second watch shows Hans to be slimy and something of a cad. Despite some reviewers, such as Gina Dalfonzo, protesting that this twist “would have wrecked me if I’d seen it as a child”, there is a long term benefit to be gleaned from this most unexpected turn of events. It boils down to being more cautious when falling in love. Often in past examples true love is established even before they speak, with the alternative being a love-hate relationship that inevitably develops positively and quickly. So it’s with a blast of ice cold fresh air that we see relationships portrayed somewhat more realistically, with practically everyone but Anna questioning Hans’ sincerity and the naiveté with which she is approaching love. This is somewhat explained in the beginning though, helping to flesh out Anna’s characterisation. But for the true feminist icon in this film, one must turn to Elsa.

The first princess to become a Queen in her own right, Elsa is cool, powerful and strong, as demonstrated throughout the film. Although hampered by childhood events, she genuinely loves her sister and cares for the kingdom. When revealed as the “Snow Queen”, she sets off to the mountains, and proceeds to blow us away with “Let It Go”, a song performed by Idina Menzel so powerfully that it transforms her into the strongest female protagonist of any Disney film, far outstripping her competitors.

However, the film is not without flaws. The princesses are both waspishly thin, with eyes bigger than their wrists and a beauty that is difficult to find anywhere in the real world. Although there is an argument that they have to be exaggerated due to animation techniques, there is no evidence of male characters being so exaggerated, and the world which these characters inhabit is exquisite, making one wonder why it would be so difficult to produce a realistically proportioned female lead. Ursula arguably represents a more realistic body shape than most princesses. Buzzfeed recently created an article lampooning the size of female eyes in Disney films, so admittedly, this is something which stretches way back, right to Snow White.

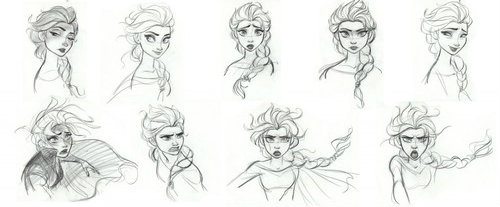

The head of animation for the film, Lino DiSalvo, also recently became embroiled in a debate about sexism when he said: “Historically speaking, animating female characters are really, really difficult, because they have to go through these range of emotions, but you have to keep them pretty”. Although Disney has said that DiSalvo’s comments were intended as the problems of technically animating a CG film, some media commentators took this to mean that female characters could not be portrayed in such a way that didn’t make them look “pretty.”

Despite these problems, the core of the film presents a definite “sisters doing it for themselves” impression, with strong female characters having a bond that, despite years of separation and minimal contact, is shown to be just as strong as any romantic love. The film is capable of bringing about a happy ending, as well as providing us with a male lead who is far from perfect, presenting a warning about being taken for a ride by people who will use and abuse you. After all, the fact that they don’t advertise it is an important part of the lesson, despite the hand wringing of concerned parents.

Comments (1)