Memoirs of a post-Erasmus student: Istanbul

For those of us returning from a year abroad, the prospect of idling about in Smack for the next year is probably less than appealing.

We’ve all had the best, and if not best, then certainly the most interesting, year of our lives and now we are back in what, compared to the likes Paris, Milan or Buenos Aires, seems like a tawdry dump on the outskirts of Coventry. I feel like an old crone as I sit at the Terrace Bar, cynically watching troops of vomit-splattered freshers unceremoniously roll down the ramp into the piazza. I’ve lost count of the number of times that friends, on having to reveal that they are fossilised fourth years, have assumed this glazed, far-away look in their eyes, as they slip into nostalgic reveries and recount their former glory days.

Having been a somewhat preternaturally judgemental and jaded fresher, my lack of sympathy for post-Erasmus syndrome has surprised friends and astounded me. I should be a prime candidate.

I think this has a lot to do with my year abroad itself and those valuable “life lessons” that seem to have given me new sense of perspective.

First of all, doing Erasmus in what is often referred to as a ‘developing’ country, Turkey, has had the effect of making me appreciate what I have at home.

In terms of student politics (rightfully a source of frustration for many) I actually think we have a fairly good union culture at Warwick that is, on the whole, democratic, representative, visible and accessible. My Turkish university didn’t even have a student’s union and the range of extra-curricular activities available paled in comparison.

The press in Turkey is not free; according to recent statistics, Turkey locks up more journalists than China and Iran put together

Perhaps more importantly, national student politics was invariably stifled. To publish a political rant in the student rag was certainly possible, but it was also something of a risk. The press in Turkey is not free; according to recent statistics, Turkey locks up more journalists than China and Iran put together.

In addition, defamation of the country’s founding father, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, is actually illegal, and I know from experience how exacting they can be about this. A young online magazine I worked for was contacted by lawyers suggesting we remove a comment which suggested Ataturk had died from alcohol-related causes (a commonly accepted theory), lest we get into trouble with the authorities. To my astonishment many seemingly harmless political conversations were conducted in hushed tones, friends insisting their opinions were liable to get them imprisoned.

The protests that erupted across Turkey this summer were by no means student protests, but you’d be hard pushed to find a student who did not sympathise with them, even if they were too scared to partake. Protests in Britain are mostly ignored by the powers that be, and the worst conceivable eventuality is a student getting roughed up by police and/or arrested. In Turkey everyone and their granny was getting tear-gassed, irrespective of whether they were rioting, protesting or simply walking home after work. Water cannons were frequently used and police aggression was a given.

While thousands were injured, a few students actually died. Due to the pluralistic nature of the protests themselves, they could have died objecting to issues surrounding topics that varied from city planning, neo-liberalism, democracy, personal liberty, to ethnic oppression, and dare I say it, seemingly whimsical issues like roads, parks and alcohol consumption – things that we don’t even bat an eyelid about at Warwick.

This leads me to drinking and sex. Much like the English, Turkish students know how to have a good time, but when your government is trying to ban the sale of alcohol within 100m of ‘religious or educational facilities’ in a city ram-packed with mosques, you’re essentially facing prohibition. Alcohol was not permitted on campus, and the two watering holes near campus made Kokos seem trendy. Students had to travel over an hour into the city centre to get a decent beverage.

Because the culture is more socially conservative, young people often don’t leave home until they get married. You are considered to be, and frequently treated as an adolescent in Turkey; whereas at Warwick, you are afforded a much greater degree of independence and responsibility.

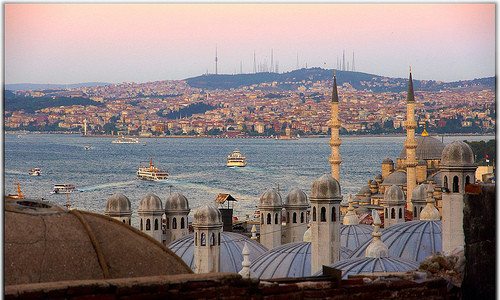

Now if this sounds like a rant about all the things I couldn’t do in Turkey, it shouldn’t. I fell head over heels in love with my temporarily adopted homeland and I’d much rather be speed boating down the Bosphorus, raki in hand, as the sun sets over two continents, than boozing on the U1. But I am pointing to issues that students can face in other countries, and that we don’t even register here.

Granted, Warwick can seem like the dullest place on the planet at times, but we can feel safe in the knowledge that we are building towards a (hopefully) bright future as employable Warwick graduates, and we can try a myriad of new things at the drop of a hat. Above all else, we also have the freedom and opportunity to develop and be ourselves.

Comments (1)