Horror In Disguise: The Before Trilogy

John Darnielle introduces the little-known Mountain Goats’ song about the breakdown of communication in a relationship, ‘Star Dusting’, by describing it as a “horror story”. This phrase and the song’s lyrics constantly echoed through my mind this year whilst watching Richard Linklater’s latest film, Before Midnight, the third in what has now become the critically acclaimed Before trilogy. Observing the arguments between two characters to whom I felt very connected, whom I had seen grow and grown up with, was nothing short of horrific.

I first saw Before Sunrise (1995) and Before Sunset (2004) when I was fifteen and immediately resonated with them, as any young wannabe romantic would. The appeal of French Céline (Julie Delpy) and American Jesse’s (Ethan Hawke) romance is difficult to convey. They meet by accident on a train passing through Vienna in the first film. After a remarkably honest and interesting conversation, they decide to spend the night walking and talking in Vienna before both must depart in the morning. It’s the very definition of a whirlwind-romance.

Before Sunset continues nine years later, where their promise to see one another again has been broken. Unable to overcome the momentousness of their meeting, Jesse has written a book about his one night with Céline with which he is touring. It is because of this he once again meets Céline in a Parisian bookshop. Inevitably the two find themselves walking through yet another beautiful European city, discussing life, love and their feelings towards each other (no surprises as to what those are).

Now if you’re willing to pull your cringing body up from the pile of sick it lies in, I will explain why these two films are so phenomenal and not the collection of romantic clichés I have no doubt made them appear to be. Like most films, the writing is paramount; Linklater takes a lot of the intellectual and philosophical ideas present in his debut Slacker (1991) and to a lesser extent Dazed & Confused (1993) and provides them with a more solid framework by filtering them through the viewpoints of Jesse and Céline. Indeed, Before Sunrise functions very much like a narrowing-down of Linklater’s first two films; the plot-less Slacker is based around loosely connected vignettes with no main characters to speak of, whilst Dazed & Confused features an ensemble cast with many interconnecting storylines centred on the last day of an American high school in 1976. Although the cast is reduced to two main characters in the Before films, Linklater maintains the ability to cover many topics by deftly constructing the dialogue to flow from one subject to the next, facilitated by the complexity of the characters.

Now if you’re willing to pull your cringing body up from the pile of sick it lies in, I will explain why these two films are so phenomenal and not the collection of romantic clichés I have no doubt made them appear to be. Like most films, the writing is paramount; Linklater takes a lot of the intellectual and philosophical ideas present in his debut Slacker (1991) and to a lesser extent Dazed & Confused (1993) and provides them with a more solid framework by filtering them through the viewpoints of Jesse and Céline. Indeed, Before Sunrise functions very much like a narrowing-down of Linklater’s first two films; the plot-less Slacker is based around loosely connected vignettes with no main characters to speak of, whilst Dazed & Confused features an ensemble cast with many interconnecting storylines centred on the last day of an American high school in 1976. Although the cast is reduced to two main characters in the Before films, Linklater maintains the ability to cover many topics by deftly constructing the dialogue to flow from one subject to the next, facilitated by the complexity of the characters.

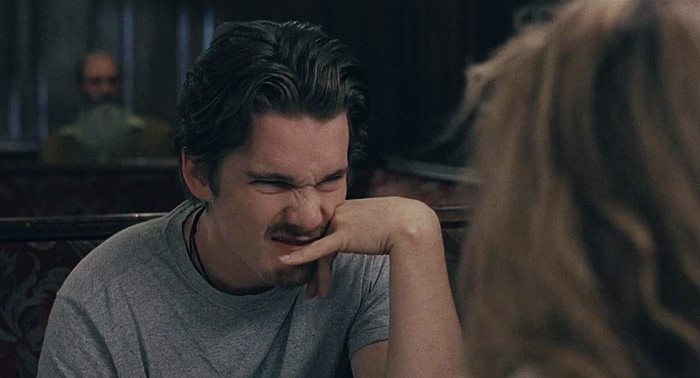

And this complexity is made abundantly clear through the quality of Delpy and Hawke’s performances. They render lines that in other contexts might appear heavy-handed into something both subtle and honest. Furthermore, Linklater’s trademark unobtrusive and passive direction allows the performances and thus the characters to really shine; one of the most memorable scenes from Before Sunrise is a long take where Jesse and Céline listen to a record in the back of a music shop, furtively looking at each other when they think the other isn’t before looking away.

The unobtrusiveness of the direction and the way in which the stellar performances are able to accentuate the script’s natural changes in topic can be seen most clearly throughout Before Sunset (which, along with Before Midnight, was co-written by Delpy and Hawke). Before Sunset is a tour-de-force of real-time editing, the film itself being little more than a single long conversation as Céline and Jesse walk through Paris, where the complex intellectual talk only momentarily halting as Céline breaks off mid-sentence, points and says “This way.”

Before Sunrise and Before Sunset became the high watermark by which I would measure my own romantic relationships. I was Dorian Gray and these films were the book Lord Henry gave him which told the story of his life before he had lived it. Whenever my own conversations or experiences aligned with those depicted in these films – such as the day I spent walking around London with a girl, constantly engaged in conversation except from when she would break off to declare a direction to walk in – I knew I was in love.

It was with this same girl I first saw Before Midnight. Another nine years have passed and since the end of Before Sunset Jesse and Céline have finally got together. They have beautiful blonde twin daughters and are holidaying in Greece at a writer’s retreat due to the success of Jesse’s literary career. The film is successful for all the same reasons as its predecessors; one scene near the beginning after Jesse drops off his son from his previous marriage at the airport is a long take of Céline and Jesse driving back which lasts over ten minutes and is never once uninteresting. Unlike the other films, Before Midnight introduces an array of characters with which Céline and Jesse individually interact with at the beginning of film, adding another layer of complexity to their characters and a contextual view of how their relationship has affected them. Everything seems to be going fine.

And then the arguments start. After bidding his son farewell, Jesse voices the thought of perhaps moving his family to America in order to be closer to his son. This, along with the jealousy borne from Jesse’s success and that success being due to Jesse writing about their personal lives, transforms the once almost wholly sympathetic and relatable Céline into an irrational monster who launches into tirades regarding her

unwillingness to live in Chicago and buy peanut butter. The most heart-breaking scene of the film shows how what was supposed to be a romantic night in a hotel dissolves into one huge argument; after Céline leaves, Jesse observes the wine they were supposed to be drinking as if contemplating how the night should have been. It’s convincing. Believable. Inevitable.

unwillingness to live in Chicago and buy peanut butter. The most heart-breaking scene of the film shows how what was supposed to be a romantic night in a hotel dissolves into one huge argument; after Céline leaves, Jesse observes the wine they were supposed to be drinking as if contemplating how the night should have been. It’s convincing. Believable. Inevitable.

When I was younger, I never understood how two people in love could argue. Why would they? If you love someone and someone loves you back, that should be the end of it – everything is perfect and you live together happily ever after etc. Over the past year I’ve become acutely aware that this is not the case.

Being in a relationship with someone, especially for a long time, and having to negotiate your love with the practicalities of living can give rise to a whole plethora of issues which result in arguments. The reality of these arguments seems even more apparent after Before Midnight. Seeing two believable characters that were so in love, and still are, argue so venomously confronted me with the horror of the inevitable breakdown of communication in relationships.

But this is not the end. As Céline relents and allows Jesse to continue his charming if immature attempt at reconciliation, the camera pulls back, revealing just how beautiful the Grecian café they sit outside is in the moonlight. The Before films have never been much for definitive endings, but Before Midnight ends with the greatest amount of hope for the future. The communication in their relationship may have broken down, but it seems as if the damage is not irrevocable. The bright hope of reconciliation is the only thing I can cling onto in the face of the horror.

Comments