A Merk-y business: Is the U.S. trustworthy?

“[W]e are not just collecting information because we can”, said White House spokesman Jay Carney, in the midst of embers following the NSA revelations, “but because we should”.

National security has always been an omnipresent motive. It was only when the Cold War ended, heralding a new unipolar world order with only one remaining superpower that frantic discourses of national security quietened. Then 9/11 fully returned it to the fore.

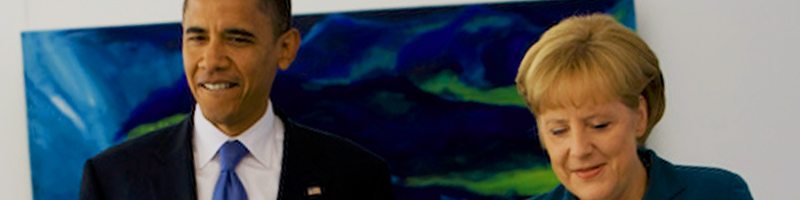

Yet there is no apparent link between Angela Merkel’s Nokia with the issue of US national security. What purpose would it serve to see the contents of her texts, and to know who she had been sending messages to? Her predecessor Gerhard Schröder was also the subject of American eavesdropping, as was France’s Jacques Chirac, when both men joined with Russia’s Vladimir Putin to frustrate Washington’s attempts to win over the UN Security Council before the Iraq invasion. It resembled an America somewhat returning to a Cold War mentality, seeing nothing but suspicion.

So why did the National Security Agency (NSA) see fit to spy on Merkel’s Nokia? Contrary to Carney’s words, the answer certainly appears to be because “we can”. It highlights a leadership that has potentially long relinquished authority over its intelligence services.

While German newspaper Bild am Sonntag insisted that Obama personally authorised the bugging, US officials exonerated him from the scandal, stating that he was not, and never was, informed. This raises the following questions: how does the US President not know what his own intelligence services were up to? Were the intelligence bureaucracies operating practically without proper political oversight, from congressional committees to the Executive itself?

How does the US President not know what his own intelligence services were up to?

To exonerate the President from blame is also to raise questions of Obama as a leader, and does nothing to ameliorate the allegations of US intelligence and security agencies as rogue bodies. While the reality may not be as dramatic as the word “rogue” suggests, it is certainly a system that has grown too large in the previous decade, and too careless about whose data collection is worth seizing.

The issue of trust thus arises between Washington and its allies. The pronounced German outrage is a remarkable shift from the euphoric days of 2008 when Obama as a presidential candidate stood in Berlin to announce a foreign policy vision of greater cooperation and multilateralism to an enchanted crowd at the Brandenburg Gate, ironically just a stone’s throw away from the US embassy where tapping operations occurred. The writing on the wall is the impression that outside the Five-Eyes circle (comprising Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand), “outsider” allies are not trusted as such, and somehow an Obama promise to Germany has been severed.

The United States will attempt to rectify this “trust deficit” and reputational damage by promising reviews and vague congressional- backed rules and legislation for the NSA to operate on, but the trust deficit is not confined to the theatre of data collecting.

Before Obama’s aforementioned 2008 speech in Berlin, he visited the Middle East with a determined rhetoric against the Iranian nuclear programme, promising to Jewish voters an “unshakeable commitment to Israel’s security”. Yet even this looks worryingly hollow for Israel, from the moment it looked as if there was a détente and even reconciliation on the horizon for US-Iranian relations. Arab nations fear this, though on the lines of Israel being a potentially uncontested nation, and fears of a more emboldened Iran promoting more diffused sectarian clashes across the region.

Though Obama seeks to execute his desired foreign policy style of diplomacy before guns, with Rouhani a prized chance to pursue peace in the Middle East, he is risking widespread alienation of traditional regional allies such as Israel, while constricted by circumstances elsewhere.

Obama is domestically pushed into continuing the War on Terror, with its dire excesses such as the Abu Ghraib prison tortures still etched in association with the United States, and the recent NSA revelations a heavy blow to the issue of trust. US-Pakistani relations remain dire as Islamabad continues to decry American excesses.The one thing the United States fear for aside from their security is their soft power worldwide. Deteriorating trust will only further deteriorate American influence.

[divider]

Photo: flickr/barackobamadotcom

Comments