Super Seventies to the Naughty Noughties: A History of the Arts

From the super seventies when the Boar started out, much has developed and changed in the art world. The seventies signified the end of easily definable artistic movements and today perhaps we are even post-postmodern. Since the 70s theatre has moved from all productions of Shakespeare being played in Elizabethan costume to wacky, experimental conceptions of the Bard’s work. How might Warwick students through the decades have seen the art world?

70s – Rebekah Ellerby

The Boar conceived during a period of growing political chaos in Britain; rising crime and unemployment, and the troubles in Ireland all prompted a heyday of political theatre in the 1970s. David Edgar wrote about a peculiarly British form of fascism in Destiny. Marginal sectors started to gain a voice and women’s theatre groups – with Caryl Churchill taking the lead – popped up everywhere. The term ‘Performance art’ came of age in the 70s.

Rock musicals flourished, with Andrew Lloyd Weber’s debut Jesus Christ Superstar, and The Rocky Horror Show’s first ever performance. Stephen Sondheim was a major influence with clever lyrics and experimental rhythmic writing; the year of the Boar’s inception he wrote ‘Send in the Clowns’. Enough said. At the time, after the London run of a musical it would tour as a much shabbier version. Now highly standardised when their rights are sold, musicals have become possibly the most globalised form of art, dubbed ‘McTheatre’ because of comparisons made with the McDonalds franchise.

The art world in the 70s is seen as the last of the easily classifiable artistic movements. The modernist era – and its buddy, Pop Art – ended early in the decade, and in its wake postmodern and installation art came to the fore. James Stirling established a wave of Neoclassical architecture with large-scale urban projects that came to be described as postmodernist, though he himself rejected the term.

The 70s serve as a transitional period into artistic modes that we perhaps take for granted in what we call contemporary art today.

80s – Harley Ryley

Imagine a University of Warwick student in the 1980s. Apart from a horrific perm, and perhaps some highly fashionable leg-warmers and shoulder pads, the truly artistic student was about to gain some great new opportunities at Warwick. In 1986, with the opening of the cinema at Warwick Arts Centre, we can perhaps imagine a trip to see Batman.

The Mead Gallery, on the other hand, may have seen the very first live-art installations, which emerged in Britain in the early 80s. Franko B, who performed live art recently at the Arts Centre was studying at art college when the Mead Gallery opened in 1986. The Brotherhood of Ruralists evoked a new era of rural art, reviving traditional methods of painting and addressing social questions.

The clan of neon clad students could perhaps have travelled to London to see any number of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s ever-growing list of musicals, including The Phantom of the Opera and Evita. This was the era that West End musicals started to go truly global.

90s – Louisa Ackermann

The 90s art scene was dominated by the Brit-Art movement; characterised by use of shock tactics, wild living and an attitude described as ‘both oppositional and entrepreneurial.’ Among the lead artists of the decade was Tracy Emin with her Turner Prize nominated piece My Bed; a double-bed stained with bodily secretions and various other detritus. The piece earned prompt notoriety, becoming a symbol of political power and unrepentant female sexuality to some, or of utter absurdity and the degradation of what art entails to others. Damien Hirst similarly became a prominent artist in the 90s, causing outrage with his infamous shark in a tank work.

According to Germaine Greer, the feminist who was a lecturer at Warwick, the 90s were a time for ‘women to get angry again.’ Perhaps this is in part because of the growing increase of ‘laddism’, defined in music by drug-happy lotharios such as Oasis, on TV in sitcoms like Men Behaving Badly and with the birth of a new kind of print culture; the Lads’ Mag. In an angry retaliation the Spice Girls shouted about Girl Power; their particular branch of liberation characterised by pinching the bottoms of royal princes and being anything but ladylike.

00s – Rachel Bradley

In the art world, nothing happened in the noughties that could possibly top the opening of Tate Modern, the world’s largest modern art gallery. For the first time in Britain the work of modern giants (think Dalí, Rothko and Warhol) were displayed together under the same roof. The galley’s unique ‘turbine hall’ – a colossal 3,400 square metre space – has played host to no less than an enormous sun (Ólafur Elíasson, The Weather Project), the Arctic (Rachel Whiteread, EMBANKMENT) and even an earthquake (Doris Salcedo Shibboleth) all in the space of ten years. Today, the former power station on London’s Southbank, attracts over 5 million visitors a year.

Darcy Bussell is a national treasure – fact. But in 2008, after 20 years of performing with the Royal Ballet, the beloved ballerina took her final bow at the Royal Opera House. Hailed as the most gifted ballerina of her generation, Bussell danced her very last dance as the lead in Sir Kenneth MacMillan’s Song of the Earth. “Generally if one individual leaves the ballet world no one really notices…but Darcy is more than an onstage performer, she’s an entity, something colossal” said Billy Trevitt, The Ballet Boyz.

Darcey Bussell’s Retirement, Carlos Acosta and Gary Avis curtain call for “Song of the Earth”, 8 June 2007, photo: Wikipedia

Despite a great recession, the noughties saw something of a theatre boom: in 2000, 11.5 million people attended West End theatres but the end of the decade, that figure had topped 14 million for the first time ever. In hard times, it seems, people want to come together, and when the National introduced the Travelex £10 season to make its theatres more accessible, attendances climbed to 93 per cent.

10s – Rebekah Ellerby

The beginning of this decade saw art becoming opening its arms to the people. Art Everywhere launched posters across the country in 2013 of great, British art voted for by the public, including 3 in Leamington Spa and 7 in Coventry city centre. As part of the Olympics in 2012, the RSC’s World Shakespeare Festival explored Shakespeare’s status as a world playwright.

Perhaps the biggest news in the arts over the past few years has been the huge cuts to funding through Arts Council England the new emphasis on philanthropy in the arts.

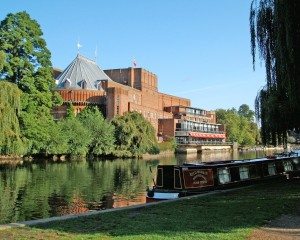

In 2011, the RSC celebrated its 50th birthday season and its transformed Royal Shakespeare Theatre was opened by the Queen, making the RSC a three theatre venue.

Royal Shakespeare Theatre from the River Avon, photo: Wikepedia

The Tate Britain caused controversy in 2013 when it opened its collections without any white plaques with explanatory details about its permanent collection.

Just 10 years older than the Boar, 2013 is the 50th anniversary of the National Theatre and we are looking into an era without Nicholas Hynter as the director of this national institution as Rufus Norris takes the helm. What the rest of the decade will bring, Boar Arts is sure to plot its course.

Comments