Roald Dahl’s Brilliance

[dropcap]W[/dropcap] hen offered a choice between the responsibilities of being 20 and at university, and the escapism of one of Roald Dahl’s children’s books, the playful works of one of the greatest children’s authors certainly presents a promising offer. From Esio Trot, to George’s Marvellous Medicine, Dahl has produced a number of classic works of children’s fiction, spawning a host of successful movies to show just how much he captured the imagination of youth. But what is it that makes his writing quite so special?

What is very quickly evident within the pages of Dahl, that makes his writing quite what it is, is an unparalleled empathy for the youthful mind. Within the first page of George’s Marvellous Medicine we can immediately see this as George’s mother says ‘so be a good boy and don’t get up to mischief’. Dahl narrates ‘This was a silly thing to say to a small boy at any time. It immediately made him wonder what sort of mischief he might get up to’. Certainly as a young boy reading his writing, I could immediately connect with the playful mischief and contempt for parental authority of Dahl’s young protagonist.

What is very quickly evident within the pages of Dahl, that makes his writing quite what it is, is an unparalleled empathy for the youthful mind. Within the first page of George’s Marvellous Medicine we can immediately see this as George’s mother says ‘so be a good boy and don’t get up to mischief’. Dahl narrates ‘This was a silly thing to say to a small boy at any time. It immediately made him wonder what sort of mischief he might get up to’. Certainly as a young boy reading his writing, I could immediately connect with the playful mischief and contempt for parental authority of Dahl’s young protagonist.

But to write good children’s fiction takes a little more than this – empathy with a child makes good reading for kids, but not quite great. The second key dimension of Dahl’s magic for me is his ability to stretch the imagination to the right degree – as a writer he never unhinges reality completely, but rather makes extraordinary things happen within a setting very much akin to the world children live in. Be it the magic of Matilda’s mental powers, or the colossal peach grown in the back of James’ garden, Dahl stretches tangible ideas rather than creating ones unrecognisable to a young child.

[pullquote style=”left” quote=”dark”]Dahl’s brilliance lies in what is perhaps the simplest of characteristics…the imagination of a child[/pullquote]

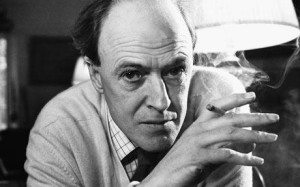

As entertaining as Roald Dahl’s writing is, all this reflection on his success begs the much more interesting question of what kind of man he really was. Dahl started his writing career writing short stories for adults about his experiences in the RAF, but with the help of his agent Sheila St. Lawrence, he was able to evolve. It was her who spotted ‘the ease in which Dahl could enter a child’s mind’, and without this twist of talent-spotting we might never have enjoyed the Roald Dahl children know and love. When looking into his life more closely, we can see many parallels between his own experience and his writing that go a long way to explain how he captured a childish mentality. For example, seeing his best friend caned by the Headteacher developed his contempt for adult authority (in Matilda, her favour famously says ‘I’m smart, you’re dumb; I’m big, you’re little; I’m right, you’re wrong and there’s nothing you can do about it’. Similarly, it is frequently retold how he slyly put goats droppings into his half-sister’s fiancé’s pipe – if this is not the kind of mischief of the young boys in his books then I don’t know what is.

Perhaps, therefore, the overriding unique point to note about Roald Dahl is that his brilliance lies in what is perhaps the simplest of characteristics. There are no significant and sophisticated literary techniques or suave methods to achieve excellent children’s literature. All that is needed is the empathy and imagination of a child – the former enabling you to create characters with which a child can associate and identify, while the latter gives the gift of plots that a child can only dream of experiencing. As a last insight, I leave you with Dahl’s very own view of what made good fiction for children – a list of traits which his works undoubtedly tick off:

Perhaps, therefore, the overriding unique point to note about Roald Dahl is that his brilliance lies in what is perhaps the simplest of characteristics. There are no significant and sophisticated literary techniques or suave methods to achieve excellent children’s literature. All that is needed is the empathy and imagination of a child – the former enabling you to create characters with which a child can associate and identify, while the latter gives the gift of plots that a child can only dream of experiencing. As a last insight, I leave you with Dahl’s very own view of what made good fiction for children – a list of traits which his works undoubtedly tick off:

What makes a good children’s writer? The writer must have a genuine and powerful wish not only to entertain children, but to teach them the habit of reading…[He or she] must be a jokey sort of fellow…[and] must like simple tricks and jokes and riddles and other childish things. He must be unconventional and inventive. He must have a really first-class plot. He must know what enthralls children and what bores them. They love being spooked. They love ghosts. They love the finding of treasure. The love chocolates and toys and money. They  love magic. They love being made to giggle. They love seeing the villain meet a grisly death. They love a hero and they love the hero to be a winner. But they hate descriptive passages and flowery prose. They hate long descriptions of any sort. Many of them are sensitive to good writing and can spot a clumsy sentence. They like stories that contain a threat. “D’you know what I feel like?” said the big crocodile to the smaller one. “I feel like having a nice plump juicy child for my lunch.” They love that sort of thing. What else do they love? New inventions. Unorthodox methods. Eccentricity. Secret information. The list is long. But above all, when you write a story for them, bear in mind that they do not possess the same power of concentration as an adult, and they become very easily bored or diverted. Your story, therefore, must tantalize and titillate them on every page and all the time that you are writing you must be saying to yourself, “Is this too slow? Is it too dull? Will they stop reading?” To those questions, you must answer yes more often than you answer no. [If not] you must cross it out and start again.

love magic. They love being made to giggle. They love seeing the villain meet a grisly death. They love a hero and they love the hero to be a winner. But they hate descriptive passages and flowery prose. They hate long descriptions of any sort. Many of them are sensitive to good writing and can spot a clumsy sentence. They like stories that contain a threat. “D’you know what I feel like?” said the big crocodile to the smaller one. “I feel like having a nice plump juicy child for my lunch.” They love that sort of thing. What else do they love? New inventions. Unorthodox methods. Eccentricity. Secret information. The list is long. But above all, when you write a story for them, bear in mind that they do not possess the same power of concentration as an adult, and they become very easily bored or diverted. Your story, therefore, must tantalize and titillate them on every page and all the time that you are writing you must be saying to yourself, “Is this too slow? Is it too dull? Will they stop reading?” To those questions, you must answer yes more often than you answer no. [If not] you must cross it out and start again.

Children’s week may be over, but the brilliance of Dahl shows us that children’s fiction can allow us to relive what made us first fall in love with books, and is a genre that should be celebrated all year round!

Comments (1)