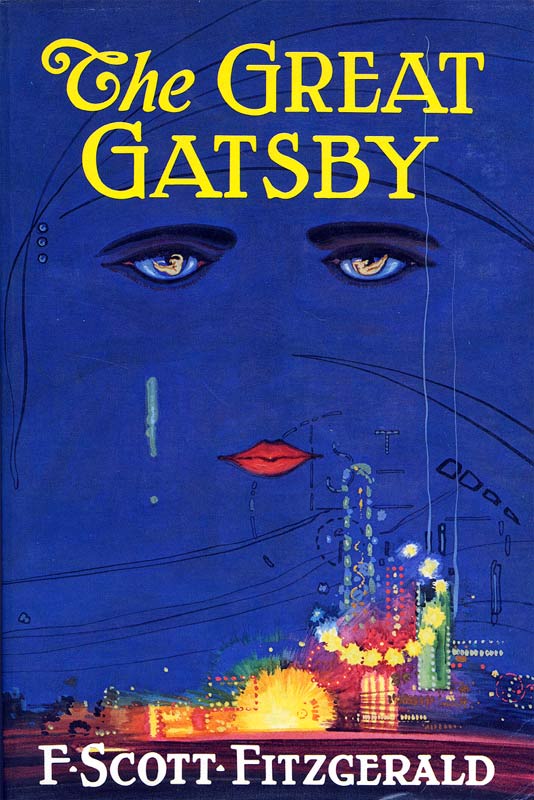

The Great Fitzgerald

Last week saw the release of the hotly anticipated film adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby: an aspirational tale of love, excess and the onset of disillusionment with the American Dream. Fevered debate has arisen over how the film fares against the classic work of literature, especially with Baz Luhrmann taking artistic licence with the soundtrack, and questions arising over whether actors Leonardo DiCaprio and Carey Mulligan measure up to the iconic characters of the book and era.

Personally, I loved the film; Luhrmann’s glossy direction, focusing on the aesthetics rather than attempting to foray into loftier themes, pays a greater homage to Fitzgerald’s world – superficial, materialistic, excessive – than some people believe. And, obviously, Leo as Jay Gatsby (those eyes! That tan!) just melts the loins of literature geeks across the world.

Whatever people think about the film, it is clear that 2013 is swiftly becoming the year of Fitzgerald. Four new books documenting his life and loves (in particular his wife, Zelda Sayre) will be published this year: Careless Fools by Sarah Churchwell; Beautiful Fools by R Clifton Spargo; Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald by Therese Anne Fowler and Call Me Zelda by Erika Robuck. These, along with articles that have been popping up left, right and centre as the film approaches, add fuel to the fire that is the current fascination with Fitzgerald. Fitzgerald’s novels were often sneered at as being little more than veiled autobiographies, and in his magnum opus, The Great Gatsby, this is more evident than ever. Does Fitzgerald manifest himself in Gatsby, the ever-hopeful charmer and tragic hero who represents the consequences of the materialism that defined the Jazz Age?

Whatever people think about the film, it is clear that 2013 is swiftly becoming the year of Fitzgerald. Four new books documenting his life and loves (in particular his wife, Zelda Sayre) will be published this year: Careless Fools by Sarah Churchwell; Beautiful Fools by R Clifton Spargo; Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald by Therese Anne Fowler and Call Me Zelda by Erika Robuck. These, along with articles that have been popping up left, right and centre as the film approaches, add fuel to the fire that is the current fascination with Fitzgerald. Fitzgerald’s novels were often sneered at as being little more than veiled autobiographies, and in his magnum opus, The Great Gatsby, this is more evident than ever. Does Fitzgerald manifest himself in Gatsby, the ever-hopeful charmer and tragic hero who represents the consequences of the materialism that defined the Jazz Age?

Or is he Nick, the moral centre of the story who enters Gatsby’s world a complete innocent, and leaves jaded with no illusions of the glitz and elaborate façade? Although in Baz Luhrmann’s film the end seems to give the impression that Nick is Fitzgerald, as he comes up with the title ‘The Great Gatsby’, Fitzgerald himself described Jay Gatsby as his imaginary brother. This may have something to do with Fitzgerald’s own romantic experiences: before marrying Zelda he fell for a rich debutante, Ginevra King, with whom he had a brief fling before she cast him aside for a man more ‘suitable’ to her class and wealth. The striking parallel to Daisy and Gatsby’s story is clear, and the sting of rejection for his money and breeding (or lack thereof) haunted Fitzgerald for the rest of his life. This is perhaps what sparked his gift in what critics called his “double vision”: an ability to experience the lifestyle of the wealthy from an insider’s perspective, and yet an inescapable feeling of never quite fitting in, forever the outsider. Is it this duality pervading the works of Fitzgerald that keeps readers and audiences around the world captivated?

Fitzgerald, like Gatsby, had reached a tragic end and the world he inhabited – sparkling but ultimately corrupt and morally bankrupt – contributed greatly to that.

This year marks a peak of what has been decades of adoration for Fitzgerald’s works and life: this film adaptation will be the sixth reincarnation of The Great Gatsby, and Fitzgerald’s life itself has been the focus of more attention than many other authors of the same era. Both Fitzgerald’s fiction and his reality are concerned with the same aspects of life that we remain fascinated by today: rare, irresistible glamour and sophistication, and a dark underbelly. In The Great Gatsby, the parties, liquor and various excursions are depicted as having an impenetrable veneer of grandeur – Fitzgerald lived his life with Zelda in much the same way. They remain fascinating to us because we are attracted to individuals that live outside social norms.

As celebrants and pioneers of the Jazz Age, the Fitzgeralds’ were certainly that; they rode on roofs of taxis and dived into public fountains if they were too hot. Their lives were an endless circus of parties, dresses, witty banter and champagne. Both Scott and Zelda were chronic narcissists and lived their lives as if someone was constantly watching: in a way their rise and fall paved the way for the celebrity culture that inhabits our world today. Our penchant for glamour is now satisfied by checking the sidebar of MailOnline and addictions to TV shows like Gossip Girl, Made in Chelsea and even, yes, Keeping Up With The Kardashians.

As celebrants and pioneers of the Jazz Age, the Fitzgeralds’ were certainly that; they rode on roofs of taxis and dived into public fountains if they were too hot. Their lives were an endless circus of parties, dresses, witty banter and champagne. Both Scott and Zelda were chronic narcissists and lived their lives as if someone was constantly watching: in a way their rise and fall paved the way for the celebrity culture that inhabits our world today. Our penchant for glamour is now satisfied by checking the sidebar of MailOnline and addictions to TV shows like Gossip Girl, Made in Chelsea and even, yes, Keeping Up With The Kardashians.

It is no surprise that people still hark back to the original and impossibly more glamorous age that The Great Gatsby embodies. However, the tragedy of both the Fitzgeralds’ declines, and Gatsby’s, add a poignant side to the seemingly everlasting glamour. Fitzgerald’s descent into alcoholism contributed to his death in 1940, at just 44, and Zelda fared no better: diagnosed with schizophrenia, she spent her later years confined to asylums, the last of which burned to the ground whilst she slept on the top floor. Fitzgerald, like Gatsby, had reached a tragic end and the world he inhabited – sparkling but ultimately corrupt and morally bankrupt – contributed greatly to that. The juxtaposition of the two elements of this world is what we remain engaged by.

This tragic tale of both Jay Gatsby and F. Scott Fitzgerald has one overwhelming message: all parties have to end sometime. Fitzgerald knew that, and ironically wrote about it in The Great Gatsby, and in many of his works without recognising the significance it would have in his own life.

Comments