“Women don’t paint very well…it’s a fact”

Baselitz’s recent claim that “women don’t paint very well” and that art should be “brutal” has caused a great stir. He is intentionally provocative. He comes across, and indeed deliberately positions himself, as a lucky and wealthy man, with such prestige that he feels he can say anything he likes and get away with it.

Although his ideas are outrageously ridiculous and can be offensive, his views force us to re-assess the impact essentialist notions of gender still have upon art and the art market, and vice versa. Some say we are in a post-feminist society, but here feminism definitely comes in handy.

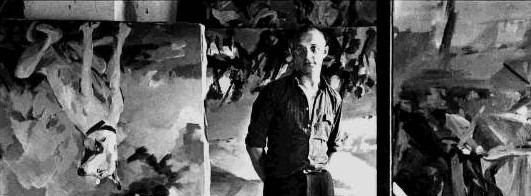

Baselitz is a German artist who emerged after the war with all guns blazing. He rebelled against abstraction, wanting to paint the chaos of post-war Germany as it was. Like many of his contemporaries, he explored what it meant to be German in a modern world filled with pain, humiliation and denial of societal and psychological traumas. He revived German Expressionism (which had been denounced by the Nazis) and re-made the human figure central in painting as a way to display harsh realities and the tragic atrocities of what man can do to man.

So when he claims “there is a lot of brutality in art. Not brutality against others, but brutality against the thing itself, against what already exists,” this is what he could mean: art is about ‘showing’, ‘confronting’ and ‘facing’ problems; it is about stabbing at what is there. In this way, he configures a bold, blunt and brutal definition of the ‘truth’ of art, what it should be, and how it should be executed.

Baselitz’s controversial statements could be seen as being born out of Adorno’s theories about good art ‘grinding away’ at an issue and being like a riddle; it is enigmatic and does not form a static or complete whole. This subtle link suggests that Baselitz is all for the viewer working meaning out for themselves: it’s about waking up rather than anaesthesia, waking up and seeing the true horror of humankind – in this case, a generation of brutalised male artists.

So when Baselitz says ‘women can’t paint’ he could mean that women artists normally work issues out in a different way from men. Often, this is done in a way that wounds them in the process.

Of course, Baselitz is wrong about women artists being ‘unable to paint’ – and more to the point, being unable to paint with strength, conviction and even ‘brutality.’ Take Paula Rego – she definitely paints without fear. There is a comparable ‘darkness’ and confrontational aspect to her work, particularly in her fairy tale paintings.

Baselitz’s argument configures art as power, and even destruction. These are both traits that are figured ‘unfeminine,’ which reveals the extent to which Baselitz is positioning painting as a masculine practice, and by extension, is defining modern art as a violent, shocking phenomenon. He does seem to rely on problematic essentialist definitions of masculine and feminine, reading men and women as intrinsically distinct, which in the end does not allow agency for either gender.

Baselitz uses the market as a strong focus for his argument. He claims women are incompetent painters because they don’t know how to respond to the demands and imperatives of the market due to their gender. So he implies ‘difference’ is sociologically inscribed in the market. By using these essentialist arguments he is trying to make his argument non-negotiable.

In this way, he emphasises how art is at the mercy of the commercial market; its values and inclinations are dictated by current trends. Although we may agree with this, judging the value of (all) art on its market value is missing the point. Painting for the art market is very different from painting for other reasons – commercial art needs to be sensational, shocking and overtly eye-catching in order to sell.

Furthermore, specifically judging women’s painting by ‘the market test’ is futile because historical, misogynistic discrimination is a dominant factor over skill that is determining its value. This gender bias seems to be entrenched in painting more than any other medium, so could this spark into debates about the hierarchical divide of art mediums and practices as a whole? If so, Baselitz is definitely treading on thin ice.

Baselitz’s argument is particularly problematic because he is not critiquing the nature of the market and its impact upon artistic practice and perception. He is exposing the market, deconstructing it and battering its logic, only so that he can place himself within it and re-inscribe gender essentialism. He is not trying to tackle any of its problems.

Indeed, he is just trying to set himself apart, as he has done throughout his artistic career, trying to throw a new perspective over things in order to make money and establish a prominent position. He is not critiquing his own privilege but attempting to add to it in a one-sided and self-interested way. This illustrates that art is ultimately about power. Baselitz is trying to stabilize this power for his own ends. So although his argument is clever, it is entirely self-serving and devious. It distorts and perverts artistic production as a whole because it manipulates and relies upon the current capitalist system.

His motive to make money is particularly pertinent because his own art suffered significantly in the market last year as collectors didn’t seem interested in any of his later work. His interview with Spiegel acts as a fresh image for him, a new advert to revive interest in his own work. It is not really about women’s painting at all, it is just about him and his ego.

Comments