Demand for Killer’s DNA

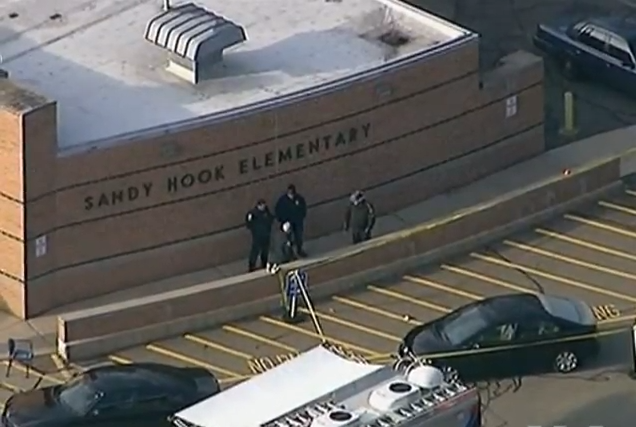

A request for a genetic analysis of mass murderer Adam Lansa, perpetrator of the Sandy Hook elementary school shooting, was placed by a medical examiner in Connecticut this week. This echoes past donations of criminal brains to neuroscience such as Peter Kurten, the ‘Vampire of Dusseldorf’ and John Wayne Gacy. Both mens’ brains were preserved and studied for clues as to what caused them to commit their crimes.

The drive to understand these massacres remains as technology advances. Today, rather than examine the structure of the brain, geneticists at the University of Connecticut will mine Lansa’s genome for insight into his behaviour. While the benefits of this exercise seem obvious given the senseless nature of these crimes, the search for genetic markers of human aggression alone will yield as little information as previous investigations of brain structure.

While no one realistically believes in a ‘mass-murderer’ gene, Lansa’s genome will inevitably yield genetic variants and alleles (different versions of a gene) which could be associated with mental illness. There are certainly links between genetics and mental illness and, by extension, violence. A Swedish study indicated that children born to men older than 60 are more likely to commit violent crimes than children born to younger fathers, a phenomenon possibly linked to accumulated mutations in sperm cells. Genetic markers have been found to be associated with autism, depression and schizoid spectrum disorders.

However the method of simply associating a specific variant with a trait is highly uninformative and does not imply a causal link. The associations made between mental health and genetics rarely hold simplistic one-to-one relationships, particularly when associated with complex traits. For example, many disease markers are carried by completely healthy individuals and conversely many people with mental illness carry no known risk factors. Something as simple as a DNA sequence cannot single-handedly explain something as complex as human behavior. They leave out vital factors such as early environment, complex synergistic gene effects and actual penetrance (the degree of expression) of the gene. Not to mention that a DNA sample from one person is not going to yield anything statistically significant. Any variations found are likely to tap into dangerous tendencies to oversimplify, particularly in the wake of tragedy. People who carry similar genetic variations could be stigmatized by their DNA, even if the variations are only associated with eye colour, harking back to the darker field of eugenics prevalent in the 19th century.

The research, which must form a piece of a must larger picture, needs to go beyond the simple desire to unpick the nature of human impulses. If appropriate expectations and clear heads are maintained, the study may yield some benefits. Genetic research, along with research into environmental development factors, could bring us closer to understanding what causes people to commit these violent crimes.

Comments