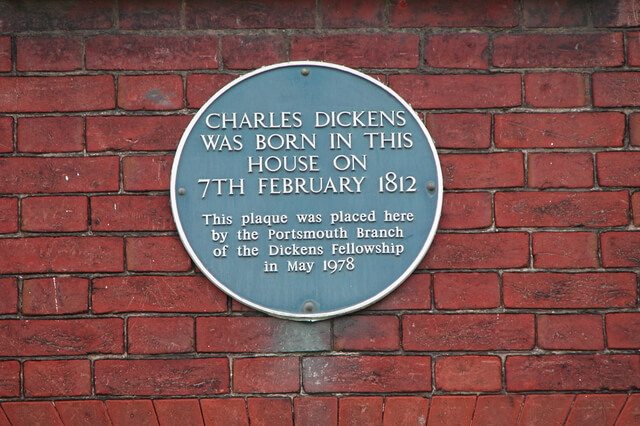

Dickensian’s Bill and Nancy; disturbingly romanticised

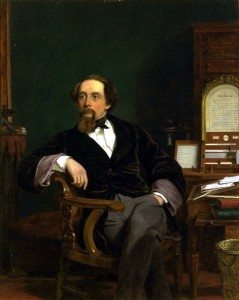

[dropcap]B[/dropcap]BC One’s current period drama Dickensian – a soap opera imagining a world in which Dickens’ various characters interact and influence each other’s lives – is filled with implausible aspects.

The series creator, Tony Jordan’s, attitude to historical accuracy, subtle characterisation, and whether the storylines even make sense in accordance with each other (they don’t) is gleefully irreverent. For the most part, these improbabilities are what make the show as guiltily enjoyable as it is.

However, there are other points where this attitude of “fun storytelling above all” runs the programme into some murky areas. The characters’ approaches towards social issues are – of course – profoundly Victorian, and the show relishes in honouring these beliefs as motivation for their behaviours, while simultaneously poking fun at them.

But the programme’s overall lack of subtlety means that, often, the serious (and ongoing) problems it throws up cannot be treated with the thought and care that they ought to be.

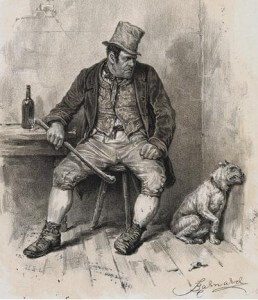

The decision to incorporate Oliver Twist’s Nancy (Bethany Muir) and Bill Sikes (Mark Stanley) into the narrative makes sense, and the show attempts to provide some background for the duo’s relationship before the events of the book.

This relationship is imagined as a romantic courtship, with Bill posed as a romantic, Byronic hero: awkward, proud, but ultimately devoted. So far, he has been shown buying her a picnic and unsuccessfully trying to purchase her freedom from Fagin. There may also have been violin music.

While the courtship itself makes sense in relation to where Bill and Nancy are positioned in the novel, the romanticising of it is disturbing.

This is not just a problem within the boundaries of the fictional realm either; Bill’s character page on the BBC website reads: “There’s only one person in the world who could possibly tame Bill and that’s Nancy, but to get her he’ll have to get past Fagin first.”

The trope of the violent man who must be ‘tamed’ by a loving woman is one which haunts our perceptions of domestic violence today, and it and seems troubling in relation to how Nancy and Bill’s relationship ends in the novel:

“It was a ghastly figure to look upon. The murderer staggering backward to the wall, and shutting out the sight with his hand, seized a heavy club and struck her down.”

It is worth noting that some have argued that Dickens’ impassioned renditions of this scene at public readings contributed to his death. Should Bill, then, really be considered a ‘troubled hero’ by the show and its viewers? And if not, why is Dickensian so keen to prove that he is?

This is not to say that stories of domestic abuse should be sidelined by popular drama. If anything, these stories ought to be told more frequently – domestic assault remains a worryingly common problem, and TV should not shy away from ‘taboo’ subjects for the sake of ‘taste’.

However, nor should these stories rely on outdated concepts of what abuse looks like. Depicting Bill and Nancy’s courtship in a thoughtful and layered manner might have given Dickensian a valuable means of engaging with a social issue that is not confined to Victoriana, but the show’s overall lack of subtlety means that a valuable opportunity to treat the narrative with consideration is again lost.

It will be interesting to see how future episodes play out Bill and Nancy’s relationship, but at a time where the BBC’s BAFTA-winning 2014 drama Murdered by my Boyfriend is circulating on iPlayer again, it seems that a big step backwards has been taken.

Comments