The weak trope of the strong female character

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he trope of the ‘strong female character’ has more damaging implications than the term may suggest. It often occurs that this kind of character merely becomes another form of stereotype, one which is paper thin; behind their strength there is no depth to them as individuals.

When a female character is ‘kick ass’ and yet serves no other purpose, or gives no indication of emotion other than ‘angry killing machine’, this can be just as degrading as a woman who exists in fiction merely as an object of sexual desire. It is always brilliant to see strong, assertive women who can hold their own on television, but in order for these characters to be truly empowering, they must also be more multifaceted.

Real women are a mixture of all kinds of personality traits, both contradictory and complex, and strength and vulnerability can certainly exist simultaneously within an individual

This is what was so refreshing about Buffy the Vampire Slayer when it aired. Buffy (Sarah Michelle Gellar) herself is the kind of character who could fall into the ‘strong female character’ trope in the wrong hands. She could easily have been a closed-off ice queen who knows how to land a pun equally as powerful as her punches during fight scenes.

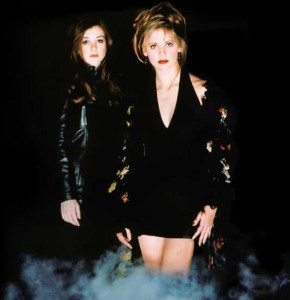

Photo: Willow (Alyson Hannigan) and Buffy (Sarah Michelle Gellar) – Flickr/Purple Slog

Joss Whedon avoids this however: of course the puns are present and – yes – Buffy does have moments of coldness (don’t we all?), but at the same time she is continually presented as a deeply empathetic individual who is in touch with her emotions. Indeed, the show stresses repeatedly that it is this emotion that provides her with true strength. Over the course of the series, she repeatedly makes mistakes and the characterisation is so strong that these never feel like obscure plot twists; Buffy is so well developed that the audience is always able to understand her reasoning and empathise with her.

What is therefore encouraging about the modern televisual landscape is that these kinds of female characters seem to be far more frequently seen; indeed, a recent article in The Independent declared that this was the golden age of the television heroine. Whilst ultimately accurate representation across all fictional mediums, including film, is the ideal, it seems unavoidable that currently the best place to go for complex and captivating female characters is television.

The two shows which immediately spring to mind considering this are Orange Is The New Black and Game of Thrones. Although the latter show has been involved in a great deal of debate with regards to its treatment of both female nudity and rape, critiques which are indeed incredibly worthy of discussion, I believe that the female characters themselves are unarguably some of the most layered and fascinating on television today.

Upon reflection, it is fascinating that both of these shows are situated in locations (prison and a medieval era society) which don’t exactly lend themselves to the notion of feminine empowerment, and yet perhaps this is what makes these characters so compelling.

Sexism becomes a literalised institution in these settings where women are viewed as second-class citizens, and yet they continue to assert themselves

One of the most impressive aspects of this storytelling is that clear-cut lines between right and wrong become significantly blurred; there is no such thing in these worlds as somebody who is wholly good or wholly evil. As such, the female characters are able to break free from the limitations of stereotype, and feel like real humans.

Photo: Uzo Aduba (Suzanne Warren) – Flickr/The Huntington

In Game of Thrones, a figure like Margaery Tyrell (Natalie Dormer) can be both a shrewd power player who knows how to manipulate those around her and simultaneously a compassionate individual who shows warmth and kindness, whilst Orange Is The New Black’s Suzanne “Crazy Eyes” Warren (Uzo Aduba) is able to launch a vicious attack on one of her fellow inmates and still show an incredible degree of vulnerability.

Ratings alone show that there is powerful demand for female-led programming. Coven, the third series of American Horror Story, without a doubt the season most directly focused on its female cast, received the most consistently high ratings the show had ever seen. The output of Shonda Rhimes, such as Scandal and Grey’s Anatomy, continue to maintain strong ratings in an American climate where network television is seeing increasingly declining viewership.

But television networks still need to ensure that the manner in which they depict these women is free of stereotypes. It would be incredibly foolish to adopt the view that the issues for women on television are resolved; there is still a great deal of work to be done with regards to representation, not only for women but for all minority groups. However, it does feel as though there are significant and powerful changes taking place. The ‘strong female character’ is gradually evolving into the real female character, and this is most certainly something to be welcomed.

Comments