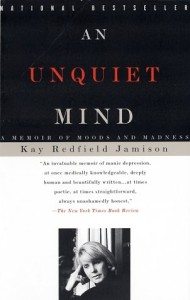

Jamison’s ‘Memoir of Moods and Madness’

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]inston Churchill used to compare his frequent bouts of depression to an ever-present black dog. These dogged lows are only one pole of the spectrum for those who also experience exuberant highs – in other words, those who suffer from bipolar disorder. Another name for this condition is manic depression, the term preferred by Kay Redfield Jamison.

Jamison literally wrote the book on manic depression, in the form of textbook Manic-Depressive Illness, a scholarly work that is still frequently cited in the scientific literature. She has spent her life practising medicine and psychiatry, and throughout much of her life in psychiatric practice she kept hidden the fact that she suffers from the very demons that she was trying to tame in others. An Unquiet Mind was her ‘coming out’ memoir, and in it she tries at one point to encapsulate and capture the dream-to-nightmare dichotomy of the illness: “Manic depression distorts moods and thoughts, incites dreadful behaviours, destroys the basis of rational thought, and too often erodes the desire and will to live. It is an illness that is biological in its origins, yet one that feels psychological in the experience of it.”

It is…an illness that is unique in conferring advantage and pleasure, yet one that brings in its wake almost unendurable suffering and, not infrequently, suicide.”

One of the major problems facing mental health practitioners and researchers is accurate diagnosis. People prone to thoughtful melancholy or reasoned pessimism might confuse this with clinical depression, which is neither reasoned nor thought-inducing. Conditions such as manic depression, for those of us who aren’t afflicted by it, can even be seen in romantic terms as an elevation of normal existence into something more free, wild and daring. Retrospective diagnoses of manic depression have been applied to many geniuses from previous eras, and several celebrities have also attributed at least part of their own success to the mania that constitutes one half of the condition. This type of idealistic thinking must be resisted.

One of the major problems facing mental health practitioners and researchers is accurate diagnosis. People prone to thoughtful melancholy or reasoned pessimism might confuse this with clinical depression, which is neither reasoned nor thought-inducing. Conditions such as manic depression, for those of us who aren’t afflicted by it, can even be seen in romantic terms as an elevation of normal existence into something more free, wild and daring. Retrospective diagnoses of manic depression have been applied to many geniuses from previous eras, and several celebrities have also attributed at least part of their own success to the mania that constitutes one half of the condition. This type of idealistic thinking must be resisted.

The major achievement of this book was to find a balance between the rigorous clinical experimentation, drug trials, brain chemistry and the rest, and her personal life. Her wild shopping sprees, exquisite sensitivity to music and sex while manic, suicide attempts, and the destruction and construction of her relationships are all described in prose that beautifully counterposes artistic sensitivity with scientific rigour. She has lived through the shift in psychiatry that has gone from preferring the flimsy and convenient explanations of Freud to a larger emphasis on brain chemistry and imaging, and her prose reflects this.

Kay Redfield Jamison’s book is a wonderfully sane account of her illness.

Despite prescribing Lithium to many of her patients, she had always been hesitant about taking the drug herself. The sheer scale of her extreme moods soon made this stubbornness untenable, and she started taking the drug that she is convinced saved her life. She describes, in a beautiful phrase, how Lithium “gentles me out”.

I particularly love the moment at which she relates, mid mood-swing, her sudden remembrance of a poem written by Edna St. Vincent Millay. Jamison  had not read this poem, ‘Renascence’, since she was a child, and yet, in a sudden epiphanic moment, it seemed to her to explain and perfectly capture the ever-sharper descent into madness that she was herself undergoing at the time. Jamison at this point did not know that Millay had, after writing the poem at nineteen years of age, later survived many breakdowns of her own.

had not read this poem, ‘Renascence’, since she was a child, and yet, in a sudden epiphanic moment, it seemed to her to explain and perfectly capture the ever-sharper descent into madness that she was herself undergoing at the time. Jamison at this point did not know that Millay had, after writing the poem at nineteen years of age, later survived many breakdowns of her own.

Stephen Fry (a fellow sufferer) once asked several people with manic depression whether or not, given the chance, they would push a button which would strip them of their extreme moods, thereby rendering them normal. Passing up the opportunity to make the obvious quip (“It would depend on my mood at the time of asking”), most eventually said no, they would not. A provisional explanation for this unexpected reaction is perhaps provided by the epigraph of Jamison’s important book, courtesy of Lord Byron: “I doubt sometimes whether a quiet and unagitated life would have suited me – yet I sometimes long for it.”

Image Credits: Header (Facebook), Image 1 (Facebook), Image 2 (Flickr/Duncan Hull)

Comments