The Theory of Everything: crafting the Hawking family biopic

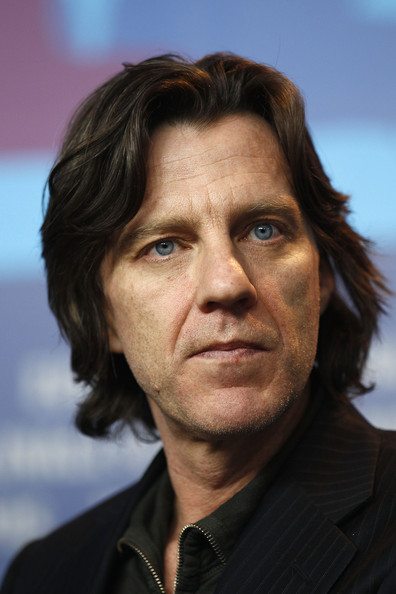

One of the most exciting British films of the year, The Theory of Everything has been garnering plenty of Oscar buzz, especially Eddie Redmayne for his astounding performance as the young Stephen Hawking. I met the director and the writer of the Hawking biopic in a room at the luxurious Claridge’s hotel in London, decorated for Christmas like a real winter wonderland. Anthony McCarten, a New Zealand-born writer for stage, screen and prose, is chatty and immediately engaging, demonstrating real passion for his subject matter behind the wise-cracks. James Marsh, a director most well-known for his documentaries such as Project Nimm and Man on Wire, is the quieter of the two, but when he does speak, his answers are thought-provoking and insightful.

“I read Jane Hawking’s autobiography [Travelling to Infinity: My Life With Stephen] in 2004, and was inspired by the incredible courage and beauty of their personal life,” says McCarten. “I was already in awe of Stephen’s achievements and I thought if we could marry the two, we’d have a shot at an exceptional film.”

McCarten’s first job was to get the rights to the book from Jane Hawking. “I had naively imagined I could do that in one afternoon with my enormous charm,” McCarten says wryly. “But it’s very sensitive material and it turned out to be quite a scary thing for someone to show up and say they want to make a movie of your life. You’re shining a big searchlight into someone’s intimate life. In the end, it took eight years for them to grow into the idea: Jane, then the children and finally Stephen.

“I had made it very clear from the beginning that I wanted script control and that because her autobiography had been unflinching, I thought her story demanded an unflinching approach. And, to her credit, neither she nor Stephen ever asked for any of the more delicate information to be taken out. I think that’s a tribute to their bravery and their honesty.”

And how did James Marsh come on board?

“We asked him,” grins McCarten. “We thought that was a polite way to do it.”

“I was under the impression that it was a biopic of Stephen Hawking and I wasn’t sure I’d be the right person to take that on,” states Marsh. “I was pleasantly surprised to find that it was something altogether different. Having Jane’s character as an equal voice in the film was a deciding factor for me: Stephen is a public figure to whom we have some access, whereas Jane’s story is not so well-known. The love story was surprising too and that really is the definition of the film, a portrait of a relationship between two people. I was surprised and delighted by the script… It was a gift.”

“James was a gift,” says McCarten. “Once he was on board, this very slow-moving project suddenly got wings. Everyone wanted to make a movie with James Marsh directing.”

James Marsh said that casting the film was surprisingly straightforward. “There’s a generation of great young British actors and actresses. Eddie [Redmayne] had just done Les Miserables… When I contacted him, he understood almost immediately what the script entailed. Once I’d met him, I was pretty sure that he was the one and everyone came on board pretty quickly after that.”

“Felicity Jones is an actress I’ve had my eye on for a while; I thought she was really interesting in Like Crazy and The Invisible Woman. I met her and we read them [Eddie and Felicity] together and they immediately worked off each other…So that gave us a lot of confidence because this was the defining choice of the film – if we cast inadequately, then the film was going to fall apart on day one.”

“Eddie was as daunted by the role as I was to make the film, which was a very good starting point. Fear makes you work. He spent time with a vocal coach, a movement coach, met people with motor neurone disease and was able to detail his performance very specifically. If you watch the film more than once, you see how detailed his performance is and how intentional everything is that he does. The physicality had to be there every day as a given for the performance to come through. Stephen Hawking said he could have been watching himself, which is an extraordinary compliment to Eddie.”

“Eddie was his own worst critic and he would often ask for another take when he felt he hadn’t done it quite right. It was uncomfortable every day for him and he had to reposition some of his muscles, to forget some and make others work in his face. But, as he always said, it was not like having the illness, because he could always get up and walk away.”

Stephen Hawking said he could have been watching himself, which is an extraordinary compliment to Eddie

When McCarten was asked how he approached the adaptation of a real-life story, he explains, “I took out the boring bits, kept all the interesting ones and fused scenes together. Those are the necessary elisions and conflations that you have to – and should – make. Sometimes you do great disservice to the emotional truth if you doggedly stay with every fact. So you work out what your theme is and you serve your theme. Our theme was time, the nature of time, and what it does to people.”

“We honour all the major scientific break-throughs. They aren’t the boring bits – the boring bits are doing the laundry and putting gas in the car. We had to suggest the enormous, dull workload of Jane in a very few scenes without labouring it. She was a Trojan and although we don’t devote a lot of screen time to it, people (especially women) come away from the movie saying that she must have been a saint to raise three children and look after Stephen.”

“Stephen hasn’t written an autobiography and was on record saying he didn’t seek any investigation of his personal life,” says McCarten. “He wanted the focus to be on his work. But fortunately there’s a lot in the public domain about him and we brought in a physicist, an ex-student of Stephen’s, to help shine light on the science. Jane’s book gave a lot of insight into Stephen, especially when he got the diagnosis. Jane showed the depths to which he sunk. Hawking’s an artist, he’s under-celebrated as a writer of prose. So something of the witty, Oscar Wilde maverick about him was probably the touchstone for me.”

Marsh adds that, “A Brief History of Time is very pithy, well-written in a simple way, because each word is an agony to produce.”

Both men agree that the feedback from the Hawking family has been overwhelmingly positive.

“Stephen, Jane and the children all felt that the world we had created was very familiar,” says McCarten. Marsh adds that, “They all praised the honesty of the depiction of the marriage, which was a very generous thing for them to say.”

Any tips for aspiring writers and directors? “Don’t do it!” grins McCarten, mischievously.

“You can spend a lifetime not working,” says Marsh. “There’s been an element of luck in my career. You can’t really manufacture luck – the main thing you need is to be curious about the world… That’s a good starting point for any creative endeavour.

“Any good idea you have comes from hard work. There’s no reservoir of inspirational genius – you have to work, work, work and then you have an idea that’s worth having,” says Marsh, but adds, “Studying the great works of screenplays and movies was how I learnt how to make films.”

McCarten adds, “Everybody I know who’s ever worked in a creative role and has been one way or another successful, would have done it without any rewards. They would have done it in the absence of money or fame – you just have to do it.”

Image Sources:

Header Image and Image 3 – UPI Media, Image 3 – © Charlie Gray

Image 1, Image 2

Comments