Warwick’s own app-wizard Ian Stewart: The full interview

An Emeritus Professor of Mathematics and Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS), Ian Stewart has been a champion for the popularisation of maths and science for over 30 years. He has written more than 20 bestselling popular science books. Stewart has now joined forces with Profile Books and Touch Press to create Incredible Numbers, an iPad app which explores the hidden patterns that numbers can reveal in the world around us. I caught up with the professor to discuss his career and this exciting new app.

You came to Warwick not long after it was founded. What brought you to the University and made you stay for so long?

I spent four years as an undergraduate at Cambridge, in Churchill College, which was very new – my year was the second intake. After graduating I wanted to do a PhD in group theory. This was one of the three main research areas at Warwick, which, even then, had an excellent research reputation in maths. I completed the PhD in two years, and was offered a temporary job for one year. After that, they made it permanent.

I’ve stayed here ever since and the reason is simple: it’s a terrific place to work in. It’s fresh, broad-minded, and the Maths Department has been a jewel in the university’s crown from day one. (Not the only one, I hasten to add. But we got started early, mainly because in those days maths was cheap.) Over the years I’ve been offered jobs elsewhere, but Warwick always managed to trump the offer in one way or another. For instance, in 1997 my teaching and admin duties were replaced by public understanding of science, and that made my timetable much more flexible, so I could appear on radio or TV without having to work round my lectures. I enjoyed lecturing, but to be honest I didn’t enjoy marking exams. And it was becoming impossible to do 50% research, 50% teaching, 50% admin, and 50% public engagement. I know it doesn’t add up, but ask any academic…

In the seventies you edited Manifold, a mathematics magazine here at the University. Could tell us more about the experience?

Manifold was great fun. We started it in 1968, soon after I arrived. The university had about 600 students then, and new ideas were generally welcomed. We persuaded friends and acquaintances to write articles (and wrote some ourselves under pseudonyms). Christopher Zeeman, the founding professor and head of department, allowed us to use the duplicating equipment. There were no laser printers in those days, not even a photocopier so we typed the magazine on stencils and printed out copies. We even collated and stapled them. He probably didn’t expect a 56-page first issue, but there you go.

Manifold lasted for 20 issues over 12 years. It had a kind of cult following – I think of it as a maths fanzine. It was scruffy but lively, quirky, and humorous. I’m putting scans on my website; so far I’ve put up the first 7 issues.

One year we made so much money that we blew most of it on the Manifold Annual Dinner. Annual in the sense that it happened in exactly one year!

In addition to a prolific academic career, you are well known for your popular science books. You have even received medals for promoting maths to the public. How important do you feel it is for scientists to engage with the general public?

Very. How can the public appreciate what mathematicians and scientists are doing – or that they are doing anything – if we don’t tell them about it? But we can’t expect them to understand the technical papers. We have to explain the story behind the research.

However, we don’t all need to do it; what’s needed is enough of us, and the support of the rest. In the 70s a colleague of mine was criticised by his Vice Chancellor for ‘wasting time writing columns for The Guardian when he ought to have been publishing papers’. That was a prevalent attitude – but not at Warwick. We were the new kids on the block, and the senior admin people understood the value of publicity. And, to be fair, the value of engaging with the public.

There was, however, a sting in the tail. Warwick was happy as long as you did all the other things that academics ought to do as well; 100 percent was never enough.

Nowadays, your Vice Chancellor is more likely to complain if you’re not writing columns for The Guardian. Outreach is recognised as being important. I’ve been on the Royal Society’s Faraday Medal Committee for the last nine years, six as Chair. It awards the Society’s main medal for public engagement. It’s now being replaced by a far more extensive Public Engagement Committee, to oversee a rapidly growing list of Society activities of that kind. This is a clear sign of changing attitudes.

Terry Pratchett named you an “honorary Wizard of the Unseen University” for your work on the Science of Discworld books. How did the series come about?

I’m proud to be an honorary wizard, it’s on my letterhead along with other lesser academic honours like FRS. I treasure my staff, with carved elephants; it hangs on the wall at home. And yes, it does have a knob on the end.

How did it happen? From about age 15 I was a science fiction fan. In 1990 I met Jack Cohen, another SF fan. I collected the books and magazines (still do); he was more sociable and went to conventions. And he’d known Terry from before he was famous. Jack carted me along to a convention in Birmingham. We were sitting at the bar when Jack suddenly shouted “Look! There’s Terry!” He’d come along not to give a talk, but as an ordinary fan. So the three of us had lunch, got on well, and Jack and I would drop by Terry’s house if we were in the vicinity.

One evening – Jack always says it was in a Mongolian restaurant – we got the idea of doing a book combining science popularisation with Discworld but Terry pointed out that we couldn’t do a book explaining the real science behind Discworld, because there wasn’t any. Discworld runs on magic and ‘narrativium’, our word for ‘narrative imperative’ (what stories want).

It took six months before Jack and I found an answer. “Terry, if there’s no science in Discworld, can you put some there?” Thus was born the Roundworld Project, which uses up massive quantities of magic to create a region where magic does not work. Instead, everything runs on obscure rules. From the outside, it is the size of a football; from inside, thanks to lack of narrativium, it does not know what size it ought to be, so it can be as big as the rules permit.

We structured the book so that odd-numbered chapters followed the wizards’ adventures, and even-numbered ones explain what was happening in Roundworld, which was science. It’s an unusual kind of fact-fiction fusion, and we like to think we invented a new subgenre.

It hit the bestseller lists (thanks to Terry) and we all agreed that it had been so much fun that we could never repeat it, it just wouldn’t work. We’ve just published a fourth one. Whenever we think of stopping, the fans keep asking about the next one. Though I’d be surprised if we ever do number five…

Incredible Numbers explores the maths behind many areas of our lives. Could you tell us where the idea for this app came from?

It came from one of my book publishers, Profile Books. Profile, like many publishers, is having to react to the electronic age, and realised that converting ordinary books into eBooks is just the start.

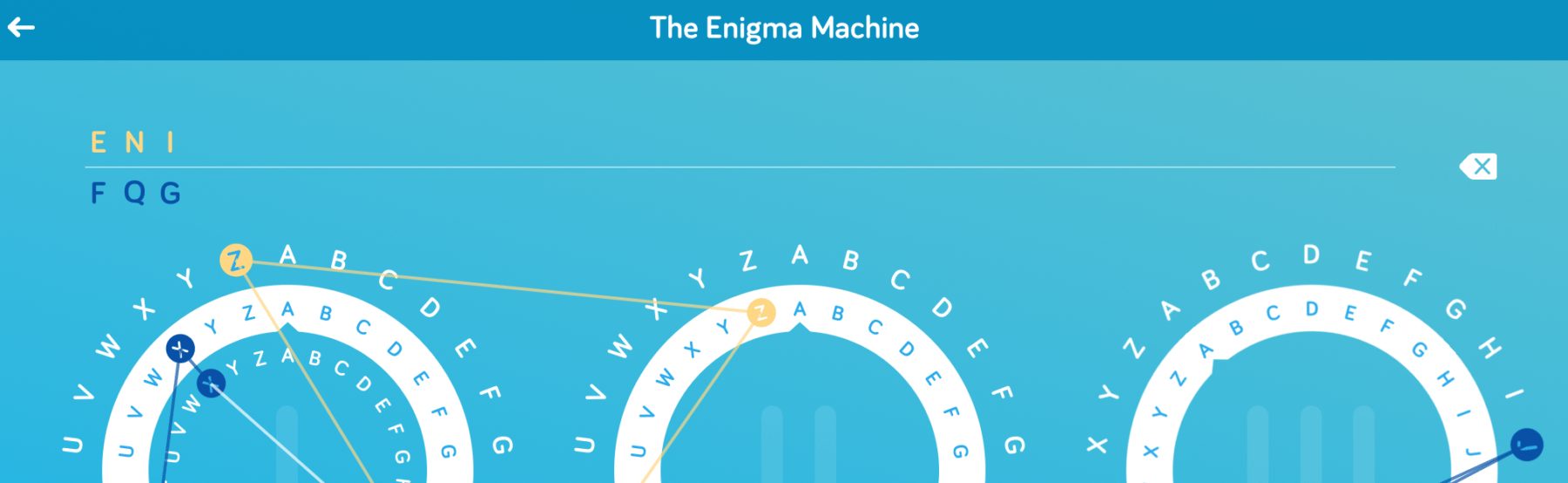

They teamed up with TouchPress, who create apps. Maths emerged as a front-runner because all sorts of mathematical topics, which seem difficult on paper, make a lot more sense when you animate them on an app and make it possible to explore them easily. My job was to supply a heap of text, from which the actual app would be selected.

The aim was partly educational; an app is a great way to interest kids in maths. It adds interest, and keeps everything friendly and non-threatening. You can have fun, and start to appreciate what maths is about. So we focused on numbers, about the simplest possible kind of material. But then we developed topics that could be presented interactively. I say ‘we’, but most of that was done by the guys at TouchPress. After all, they had to code it.

Then we had to walk the tightrope between putting in lots of cool stuff, and keeping the price affordable. And fitting everything on the screen, which is why there isn’t a phone version yet. I’m sure it can be done, but there will have to be a few compromises. So for the moment we’re focusing on an iPad version, and seeing how it goes. It’s been a rapid learning curve for all of us.

It’s got good reviews. It was the number one ‘best new app’ in the US app store when it first came out, which amazed us all. It’s genuinely fascinating to use: I’m constantly surprised by what the app can do and how fast it does it. There we had major help from Wolfram Research, who produce Mathematica. But it’s still amazing, to someone who grew up with pencil-and-paper maths, to see a freehand curve being Fourier-analysed into its first several hundred harmonics in a split second. That’s in the section on music, by the way – no technicalities. You can even listen to the sound of the waveform.

I think this is only the beginning. The way we present ideas, and how we learn new things, is going to change very rapidly. The age of stapling a fanzine together is long gone (unless it becomes fashionably retro again), and today Manifold would probably be a website. In fact, when I finish scanning it in, it will be. We’re going to upgrade Incredible Numbers from time to time, and explore other ideas for apps. Or whatever replaces them.

Comments (1)

I’m looking forward to a version I can use on my Kindle Fire!