Review: Sissay’s ‘Refugee Boy’

From the outset, poet, Lemn Sissay maintains authenticity of a culture that Britain has so little exposure to. Even before the play has begun we are met with the traditional strums of the krar, a traditional Eritrean/Ethiopian string instrument and the celebratory chant ‘lelelelele’ resonating throughout the audience; things that I, being of half Eritrean heritage, found oddly familiar.

Benjamin Zephaniah’s renowned 2001, novel Refugee Boy, is realised by the remarkable poet and playwright, Lemn Sissay in a way that can only be described as close to home. For both Eritreans and Ethiopians alike, Sissay adapts and portrays Zephaniahs ‘story’ to depict the harsh reality that these nations have faced in their numerous civil wars with each-other. However, despite its exploration of such weighty topics, the play continuously provides the humour, wit and poeticism that Zephaniah’s writing is so famous for, ensuring that without trivialising such great issues, we are reminded of the honest humanity of a 14 year old getting to grips with an accelerated manhood.

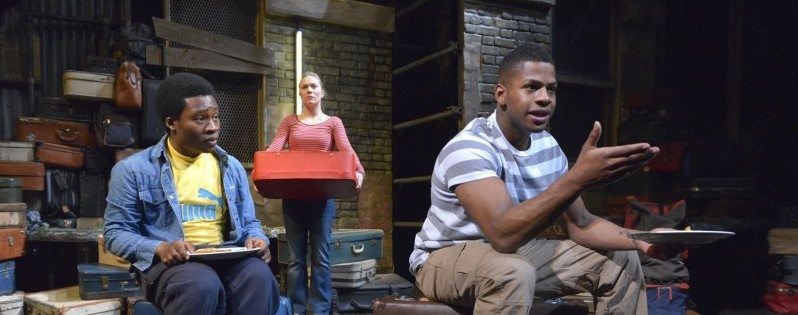

The play centres on Alem Kelo, an Eritrean-Ethiopian boy, who, in his search for safety in England, finds himself on the fringes of not only a new found European society, but of his own heritage as well. Subjected to persecution in both Eritrea and Ethiopia, Alem is in an ‘impossible situation’. Neither of his own countries wants to claim him, instead labelling him as a ‘mongrel’ and a ‘traitor’. The interchangeable roles of the more than adept cast captivate us as Dwayne Scantlebury and Andre Squire in particular switch from the compassionate teenager and father to that of a threatening soldier and hoodie who put Alem’s life at risk. Perhaps the only shortfall of Squires performance, would be that of his accent, which at times invoked either conventional African or even Caribbean intonations, rather than those of an east African.

However perhaps even more troubling than the insinuated violence, is Alem’s branding as ‘Refugee Boy’. The play underlines the ignorance and prejudice of British society, as both Alem’s fellow classmates and the court readily put him in a trite box. Alem is no longer appreciated as the insightful boy that he is, one who is captivated with Charles Dickens and the English language. He is instead simply associated with his status in a foreign land.

Throughout the play, the notion of identity is continuously addressed, whether it is cultural or personal. Through the yobbish, violent attitude that Dominic Gately flawlessly projects as the bully ‘Sweeney’, the importance that our names bear to composing each of our individual identities is highlighted. While Sweeney asserts that his name remains in its original form, he manipulates both Alem and Mustapha’s (Alem’s best friend from the care home) name to the more anglicized Ali and Musty.

The play deals with the turbulence of care homes and dysfunctional families through the characters of both Sweeney and Mustapha who are both subject to neglect by their fathers. The hyperactive aggression of Sweeney is put down to his physically abusive father; whilst Mustapha’s whimsical obsessiveness of cars is a manifestation of his father leaving him in one. Like most of the play, the comical scenes that these two loud personalities bring bear profound undertones, as Sissay and Zephaniah strike the balance between an amusing educational tale of morals and a highly politicized family drama.

The relationships that Alem forges in Britain lead us on a journey of pain and joy where we are shown of the impression that he has made on his English foster family and his campaigning community. Fisaya Akinade beautifully captures both the frustration (at Britain’s lack of knowledge of Orthodox Christmas) and the fascination (his first experience of snow) that Alem feels of the foreign land of Britain. Akinde’s gripping performance invites us into the vulnerability of a boy whose infectious laughter and delirious happiness is haphazardly cut short by the trembles of mourning for his family and home.

Sissay avoids typecasting Alem into the heart-breaking case of the refugee escaping their war torn homeland. As the Kelo family’s unique political situation is explicitly described in the courtroom by Sarah Vezmar, Sissay brings to light a conflict that has been under the radar of world media, despite the widespread threat to many families’ lives. It is why in many European countries today, we find a large community of both Eritreans and Ethiopians, each family bearing strikingly similar stories to that of the Kelo’s. It is why in Britain there are approximately 40,000 Eritreans (2008 estimate) and 20,000 Ethiopians (2005 estimate) who have sought refugee status. And, it is why, despite living in peace for decades now, people like my mother are still affected by the age-old territorial border dispute over Badme. The fast-paced drama of ‘spies’, ‘militants’ and ‘traitors’ is clearly exaggerated through the bursts of action onstage envisaged by Gail McIntyre and fast paced music composed by Ian Trollope. Nonetheless, these scenes are not as far-fetched as one would think, with the notion of an ‘eye for an eye’ being of all too common knowledge.

Almost symbolically it seems, the set designed by Emma Williams (scaffolding made from suitcases) transcends every societal situation; the war zone, the foster home, the court, and stresses that migration and travel is not as unusual as Europe’s xenophobic tendencies suggest. Ultimately Alem’s resounding message is taken from his name meaning ‘World’, as he champions a universal union of peace. Through Refugee Boy, poets Sissay and Zephiniah show us that ‘a culture of peace’ and acceptance is vital to a world where people are not limited by the nations and cultures that they represent.

Refugee Boy was performed at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre until 12th April.

Comments (2)

This is the last review. The tour has ended now. I REALLY enjoyed this review not just because it is positive about the play. It raises some insightful points.