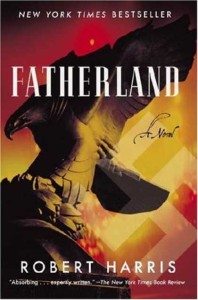

Fatherland and the Power of Alternative History

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]s I finished the last chapter of Fatherland, it took me a moment to reorient myself with reality. I had spent the better part of a week immersing myself into a very dark world where World War Two had not been won by the Allies. The sheer attention to detail, and the use of actual historical documents made Harris’ vision all the more convincing.

Reading good historical fiction is both an amazing and deeply disturbing experience. While the world we live in now is far removed from the realities of the past, it is those very events in human history that have shaped us into what we are today. And it is not until you experience a viable alternate reality that you realise exactly how much of a difference a conflict that happened decades ago really made. This is where the power of an author’s imagination is truly evident.

Reading good historical fiction is both an amazing and deeply disturbing experience. While the world we live in now is far removed from the realities of the past, it is those very events in human history that have shaped us into what we are today. And it is not until you experience a viable alternate reality that you realise exactly how much of a difference a conflict that happened decades ago really made. This is where the power of an author’s imagination is truly evident.

If any of us are asked to consider a world where World War Two had gone the other way – something that I remember discussing quite seriously in my History classes at school – the most any of us can come up with is a vague, depressed world with systematic oppression, along with a few nervous jokes thrown in about the dominance of German as the new world language. That is all we can think of – trying to imagine it in greater detail is beyond both our capabilities and our desires. Harris’s 1994 novel takes a look at the exact world we are too wary to approach.

What would the legal system be like? What about architecture? State holidays? Inter-European relations? Travel? Harris’ rich world is an achievement in itself. What he also manages to do, much more subtly, is challenge the way we take our history for granted. Not only does he make us seriously consider our perceptions of the Axis powers – the notion of history being written by the victors – but he forces us to consider facts we had never questioned before.

Namely, were the actions of the Allies, reproduced without any artistic license, free from blame? This includes considering whether carpet bombing entire cities was really the only option or whether Hiroshima and Nagasaki needed to happen. It is down to Harris’s skills as a writer that these questions are tacitly asked as an organic part of the story, and he does not create any answers. Because the truth is, there is no way for us to come up with a substantial answer to any of these questions. But, by facing these unsavoury acts of desperation and trying to come to terms with them without value judgements, we become more aware of who we are in the larger scheme of things. It is a powerful experience indeed.

Comments