Michael Landy – Saints Alive: Review

A clanking, cumbersome group of figures sway as if unable to cope with their own mechanisms, some towering far above head height. These ‘Saints’, the inhabitants inside the walls of the National Gallery this Summer, are as far from the slick androids of Will Smith sci-fi films as can be, and are all the more charming for it.

Michael Landy RA’s kinetic sculptures are an unusual choice to grace the exhibition rooms of the National Gallery, given the artist claimed during his Young British Artist years to have never been to the National, or know much at all about the history of art. Yet this exhibition is fully integrated into the world of the National Gallery. The fantastic, interactive nature of Saints Alive is not only achieved literally with the use of foot pedals and cranks to drive the mechanisms of the sculptures, but also in the sense that visitors are encouraged to seek out the original paintings that inform each sculpture – a treasure hunt of sorts. The sculptures exist as part of a network of other artworks exhibited in the National, turning what seems quite an unusual commission into an inter-textual, quirky guide to the forgotten culture of our saints.

Installation of Saints Alive at the National Gallery, 2013 © Michael Landy, courtesy of the Thomas Dane Gallery, London / Photo: The National Gallery, London

One of the best things about this exhibition is the collection of accompanying works by Landy included in the adjoining rooms. Original drawings and prints cover the walls of the gallery in the fashion of a studio, clearly showing Landy’s exploration of the mechanisms that drive his ‘Saints’. This only adds to the glorious feel of the workshop emitting from the sculptures themselves. A documentary on the Commission itself sheds light on both Landy’s creative process and on the physical practicalities of building these towering, chaotic sculptures, following their journey from cut-outs of paintings on a studio wall to physical, mobile figures. Pacing around the exhibition space feels like an obscure mixture of visiting a low-budget horror-film funfair and stumbling into Landy’s studio, mid-progress. The polished, refined world of art remains defiantly shut out by the giant oak doors of the National, polished pre-Raphaelite and Renaissance figures peering in uncertainly from the walls of the adjoining rooms out of their gilt frames.

I challenge you to watch other visitors using the foot-operated pedals attached to each sculpture without developing overwhelming sensations of fear and genuine concern for the welfare of the exhibition, along with the urge to adopt the role of art police and leap into the firing line of the clanking mechanical arms, saving the exhibits from further damage. “Don’t do that, it’ll break,” yelps your inner art vigilante. Yet there you are five seconds later at the pedal, stamping with the pizazz and vigour of a Riverdance cast member and a ridiculous grin on plastered on your face. The visible marks these statues have been inflicted with from just 3 months of their existence pose the tangible issue to onlookers of the sculptures literally self-destructing before the exhibition draws to a close in November.

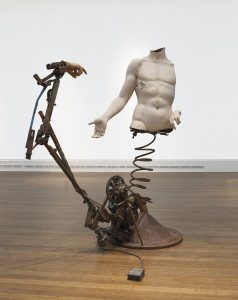

Doubting Thomas 2013 © Michael Landy, courtesy of the Thomas Dane Gallery, London / Photo: The National Gallery, London

What Landy has done here is something incredibly clever. What began as isolated idols of fable and folklore, long forgotten by the idle passers-by, Pret-grazers and tourists of Trafalgar square, are re-animated in a fashion both sinister and uniquely satisfying. With a nod to 1970s kinetic sculpture, grotesque modes of torture become literal mechanical motions to be repeated at will by visitors. This, along with the haphazard feel of the exhibition as a whole, seems to nod to an elephant man-esque fairground culture of freak-worship and a sadistic fascination with torture.

With each stamp of the unsuspecting tourist’s foot, Doubting Thomas’ finger penetrates the wounds of Christ’s torso, threatening to pierce through the torso itself with such force that it pushes the oblivious ear-plugged steward lolling against the wall behind the sculpture. Renaissance figures, the epitome of grace, beauty and symmetry, are here broken into parts; dismembered into “Frankenstein’s monsters” (Landy’s words) and subjected to repetitive, mechanical torture for the amusement of the public.

Michael Landy: Saints Alive is being exhibited at the National Gallery until 24 November 2013 in the Sunley Room. Admission Free.

Comments