The classism of closing libraries

When I speak to people about my interest in libraries, the most common responses often mention not visiting a library in years, at least not since their early childhood. People often recall happy memories of going to the library after school or at weekends, being allowed to choose any book to take home and read, before returning seven days later to repeat the process.

My main takeaway from an exchange like this is that at some point libraries were removed from the weekend itinerary, they blended with the essence of nostalgia rather than staying part of the present; meaning either the person stopped reading, or started sourcing their books elsewhere. It is important therefore to explore the shift away from the use of public books and reflect on why we choose to buy not borrow, and what that means for everyone else.

Through its fundamental property of being a civic and communal space, the public library has historically had a strong connection with the working class, belonging to a more socialist, ‘for-the-people’ politics. Much in the same way that the public health service holds no bias or financial barriers to entry, the public library has always been a space designed to serve the people — a vast majority of whom come from working class backgrounds. Providing access to books, pamphlets, journals, and more recently technology and internet, the library creates a space of learning for those who cannot afford their own.

The library is the continual crusader for egalitarian access to knowledge

The free public library made its first appearance in British culture following the Public Libraries Act of 1850, and as part of the Victorian mission to improve the public through education. There was a general consensus at the time that by reforming education and providing access to resources, institutions such as libraries could facilitate an equality of opportunity, empowering working class people to actualise their true potential and climb the social ladder. In fact, during the opening ceremony of Campfield library, Britain’s first free lending library, Mayor of Manchester, Sir John Potter, said the following:

“We have been animated solely by the desire to benefit our poorer fellow-creatures. It is the duty of those who are more favoured by fortune than they, to do everything in their power to afford additional means of education and advancement to those classes.”

Potter vocalised the true purpose of public libraries: to aid those without the means to obtain more knowledge and in turn, better lives. This is a rhetoric still present in the modern understanding of libraries. The library is the continual crusader for egalitarian access to knowledge. Much like the words on all of those pages, the meaning of the library has not changed, only slightly faded from the public domain. As author Zadie Smith said in a recent campaign to save them, local libraries are “gateways to better, improved lives”. Moreover, they represent gateways for those who cannot afford to travel that path otherwise.

Knowledge itself is a highly sought after acquisition. It connects us to the people around us, drives us toward success and enriches our lives with deeper understanding. If libraries are a hub for such knowledge, then why are they disappearing so rapidly from the typical British townscape. In the decade following 2010, 773 across the UK closed down: that’s almost 20% of the UK’s libraries.

Fewer and fewer people find themselves using libraries in their day-to-day, or week-to-week lives. Instead they rely on other institutions for their information. The expansion of the internet and online world of instant information is substantially accountable for the decreasing dependence on libraries for some of its uses; such as reference material and internet access. However, the rise of the digital world does not account for the shift in suppliers of the novel, or other hard copy books.

In an anthropocentric and capitalist world, we, as neoliberal subjects, are conditioned to obsess over the commodity

Yes, the Ebook had its moment in the mid-2010s, being foretold as the end of book publishing as we knew it. E-sales escalated alongside the popularity of digital readers like the kindle or kobo, but peaked in 2014. While the digital book did, and still does serve a certain function in the reading world (i.e reading with disabilities), the last 7 years have seen a return back to the physical in what has been coined as ‘reverse digitisation’. This return however was not paired with a return back to libraries. Instead, the public readers have spent more money on books than ever, replacing the public library with personal, at-home equivalents. This shift, I believe, largely relates to class.

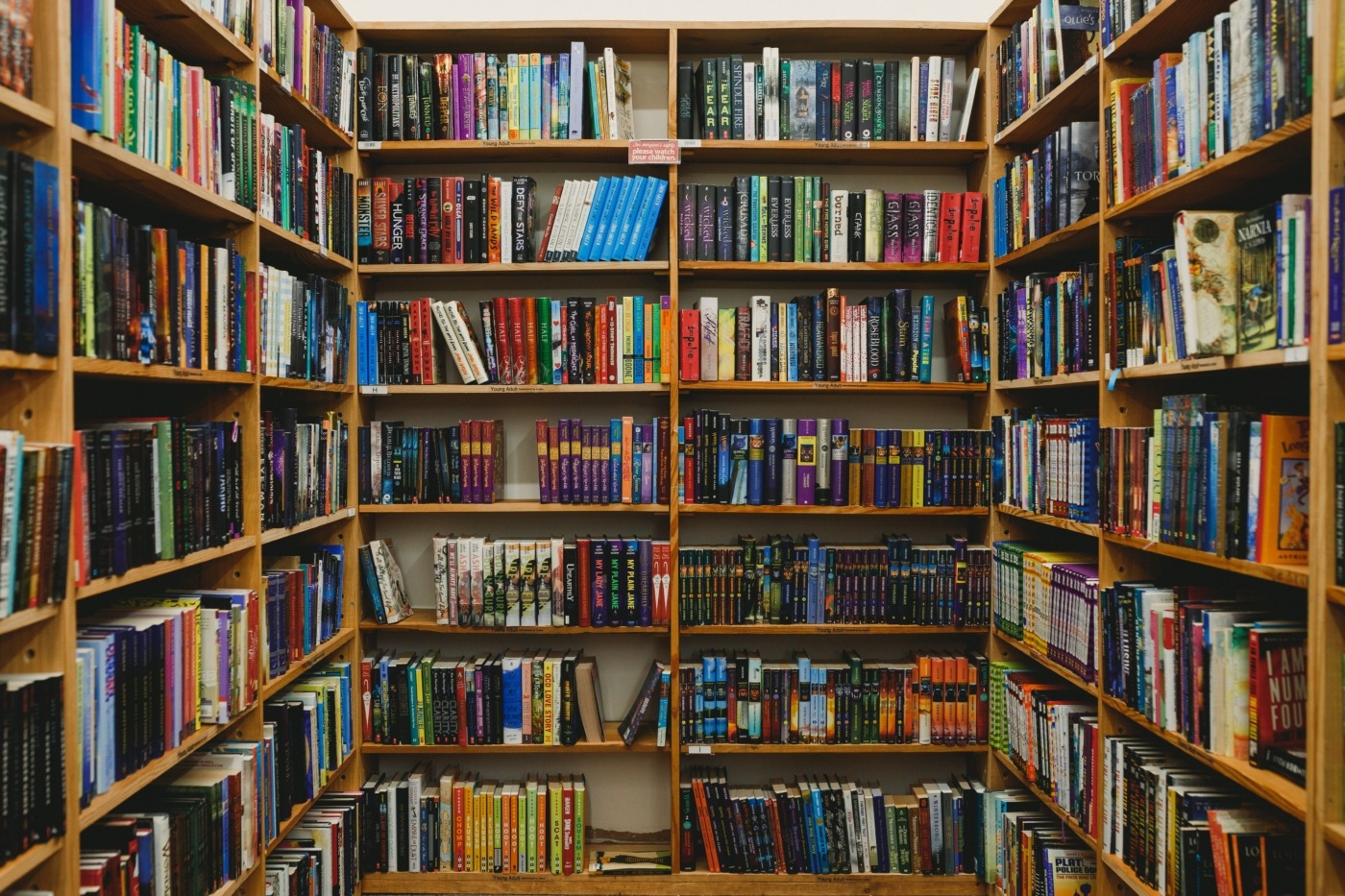

The continual commodification of knowledge plays a part in the decreasing collections of public books. In an anthropocentric and capitalist world, we, as neoliberal subjects, are conditioned to obsess over the commodity. We want to own books to prove that we belong to a class of people who read books; what we own supposedly being a mirror image of who we are. Under capitalism we are taught that class is mobile and knowledge is the key to moving up through the classes. Therefore, more and more people are buying their own books, rather than contributing to the economy of public books. It is not only that we want to gain knowledge from reading, but we need to be able to prove, or even flaunt it. We want to be able to keep and display everything we have read to prove to the people around us that we read, that we are educated and knowledgeable.

These selfish behaviours in turn impact the lives of the people who cannot afford to buy into this culture. If everybody who can afford it starts buying the books they read, then libraries will continue to lose public interest, funding and eventually fall out of business. The institutions founded with the people at its core will ultimately be destroyed by the people themselves. What we have done is deepen the class divide, destroying the egalitarian institution, and segregating knowledge so it is no longer accessible to all. While libraries become increasingly empty, we see adjacent bookshops overflowing with eager readers – the only difference is capital and ownership.

Comments (1)

Agree with much of this but I think public libraries missed the changes in society that meant shops etc were open on Sundays and Bank Holidays when families were visiting supermarkets and leisure facilities, missed advertising ‘services’ by continually promoting collections, missed delivering services much better to rural and housebound individuals, and missed reaching out via social and other media to which the nation was linked. That society is thirsty for knowledge is so clear – Google etc have snapped up that interest admirably, with ‘good enough’ results from searches, while we have prided ourselves on ‘exactness’ that mostly isn’t needed. Missed a 24/7 access to knowledge using basic teephone technology. Finally, missed reaching particularly to key decision makers, focused instead on mass numbers. There are exceptions of course, but they are a minority. We waved as the boat sailed.