A Whitewash of Biblical Proportions

2014 was reportedly christened by some to be the ‘year of the Bible movie’ and with good reason: a number of Christian-themed blockbusters were released during last year, from the Son of God that debuted in late February, Darren Aronofsky’s Noah, God’s Not Dead, Heaven is for Real, concluding with Ridley Scott’s retelling of the story of Moses, Exodus: Gods and Kings, released on Boxing Day. It would seem that this re-emergence of the Christian faith-based films will be a genre to carry on this year, with Mary, Mother of Christ portrayed by Odeya Rush, set to come out in Easter 2015; a Hollywood blockbuster that will depict the life of Jesus, Mary and Joseph under the reign of Herod the Great. Also in the works are plans for Will Smith to direct Redemption of Cain, based on the story of Cain and Abel, Pontius Pilate with Brad Pitt, and Resurrection, where a Roman soldier is sent to investigate Christ’s death.

This re-emergence of the Bible epic genre has begun elbowing through the Marvel and DC superheroes, zombie apocalypses and the tired continuation of robot franchises that have dominated the box office. Regarding Hollywood as being primarily a business, the roughly 91 million evangelical Christians in America serve as a strong foundation for huge profits. Placing their faith on the rediscovery of the Bible as a marketable subject would be savy, considering the success of the TV mini-series The Bible that averaged 11.4 million viewers and became the most watched cable show in America in 2013 and spurred the making of the film Son of God. As the figures indicate, there is a large market for those interested in the depictions of Biblical stories. Noah was as well a box-office success, making $359m in its re-telling of the building of his arc before the flood. Not only this, the source material of the best-selling book of all time cannot be underestimated; the abundance of stories makes way for many interpretive depictions, from the more apocalyptic and epic tales that Hollywood thrives off to the more humble and personal.

Noah, starring Russell Crowe, Jennifer Connelly and Anthony Hopkins, pandered to the idea of making something grand and visually stunning through the apocalyptic tale. Its tagline fits this perfectly: ‘the end of the world…is just the beginning.’ The film was a success, grossing over $43.7m over its opening box office weekend and became Aronofsky’s highest opening weekend and first film to open at No. 1. Interestingly Aronofsky described Noah as ‘the least biblical film ever made’ and saw the protagonist, Noah, as the ‘first environmentalist’. The artistic license to withdraw from the more religious elements of the film, such as omitting the word ‘God’ from the film, resulted in a backlash and questions as to why Aronovsky chose to direct a Biblical narrative in the first place.

In an interview with The Independent, he described that his retelling of the Old Testament tale was to ‘bring an original take on this content and bring it out to the world’, noting that the story of Noah is ‘pretty odd’ and ‘strange for people’. The controversy originated from early screenings where Paramount executives took an unfinished cut to Christian groups, concerned over bad publicity. Reports were mixed, some taking issue with Crowe’s portrayal of Noah in a drunken stupor, despite this occurring in the Bible, and the studio tried half a dozen cuts in order to achieve some success through the difficult formula to both allow for some artistic licensing while at the same time placating the religious groups that the film were designed to attract. The film was banned in several countries, the official explanation from Qatar, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates and Indonesia that it contradicts teachings of the Koran. For Aronofsky, his expansion and free interpretation of Noah’s story only consisting of a few pages in Genesis were from his own personal interest, and his aim was to challenge the received perceptions of the story, to ‘understand what the story means for the present day’. Recognizing the ecological parallels to global warming, and the protagonist as a hero, these themes were to bring some modernity and relevance to the Biblical epic in the Hollywood package of visual effects, bound to annoy some in the wake of the re-emergence of the biblical genre.

“I can’t mount a film of this budget, where I have to rely on tax rebates in Spain, and say that my lead actor is Mohammad so-and-so from such-and-such” – Ridley Scott

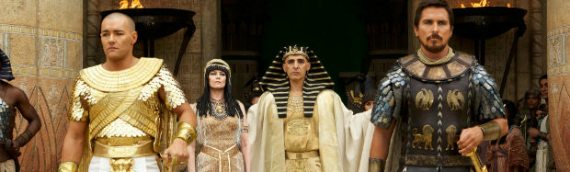

Another Biblical-inspired blockbuster to come under criticism, not just for its content but also its casting, was Ridley Scott’s Exodus: Gods and Kings, starring Christian Bale, Aaron Paul, Sigourney Weaver and Ben Kingsley, which retells the exodus of the Hebrews, led by Moses, from Egypt. The response was lukewarm, with mixed-to-negative reviews from critics on its pacing, screen-writing, and character development, overall unable to live up to the source material. Controversy ensued over statements made by Ridley Scott that he would look towards natural causes for the miracles of the parting of the Red Sea, and Christian Bale’ description of his portrayal of Moses as ‘schizophrenic’ and ‘barbaric’, resulting in concerns that the film would not be biblically accurate. Egypt banned the film due to the historical inaccuracies, followed by Morocco, United Arab Emirates, and Kuwait. In an interview Ridley Scott confirmed that Exodus was his biggest project to date but that rather than approaching it as his biggest he came to it ‘it from the point of view of the characters, of the story.’ Regardless, his emphasis was on the scale of the movie, and the extraordinary effects that allow for what occurs on screen to look real, concluding that this was going to be ‘fucking huge’ in its scope.

The major controversy over Exodus centred around the accusation of whitewashing, where the principal cast was comprised almost exclusively of white actors, getting round the issue of darkening the actor’s skin by use of fake tan. In an interview with Variety over the decision, Scott made it clear that he hadn’t even considered casting non-white actors, arguing that ‘I can’t mount a film of this budget, where I have to rely on tax rebates in Spain, and say that my lead actor is Mohammad so-and-so from such-and-such. I’m just not going to get it financed. So the question doesn’t even come up’.

The unapologetic and tactless response brought home the reality for non-white actors in the Hollywood film industry, where the stand-alone Biblical drama could not afford to cast newcomers or lesser-known actors. However, the issue of financial backing does not absolve Scott of such responsibility and the response to not have even considered casting ‘Mohammed so-and-so’, apparently his term for all non-white actors, would suggest that the issue partly lies with directors refusing to offer the chance to those who would be a fairer representation of the characters. At the film’s New York premiere, the director told critics to ‘get a life’ in the wake of his decision to cast white actors in Middle Eastern roles. Christian Bale, in response to the accusations of the whitewashed epic, stated that audience habits would need to change if actors of Middle Eastern or North African heritage can be given a chance in similarly pitched Hollywood productions.

Images: Paramount, 20th Century Fox

Comments