Does travelling make you more employable?

[dropcap]F[/dropcap]ive writers and graduates tell us why they think travelling during, before, or after university makes someone more employable.

Selina Sykes

Thought a year abroad was all about wild Erasmus parties and carefree sightseeing? Whilst you will meet new people, discover new places and have fun, you’ll also be picking up some invaluable skills along the way.

In an increasingly competitive and international job market, employers are recognising the value of a study or work placement abroad more than ever before.

The first skill that will make you stand out from the hundreds or thousands of applicants is something that I am a great advocate of: being able to speak another language.

The UK has an extremely low level of young people going on to study languages at university, which is quite surprising considering how increasingly global most sectors are becoming.

“English is the international language”, I hear you say. That may be true, but language learning goes beyond communication. It is a question of understanding and being able to interact and work in another culture – something that employers really appreciate.

Working or studying abroad makes you a more independent and confident person. Life in a foreign country presents you an array of life lessons that even two years living away from home in the university bubble cannot teach you. You will become an expert at improvising, problem-solving and getting out of sticky situations. You’ll also have some priceless anecdotes for the pub – and for interviews depending on the content!

In my interviews for masters and work placements, I was immediately asked about my year in France. Being an Anglophone abroad will automatically open doors – the vast majority of work I did was due to being bi-lingual.

So if you are planning, are currently on or have done a year abroad, take up as many opportunities as possible. Once you’ve come back, don’t just reminisce fondly about ‘that crazy year on the continent’ – put it on your CV, talk about it during interviews and make yourself stand out from the crowd.

Jenny Clark

I just spent an amazing year living in Melbourne and studying at Monash University. My first week was deservedly spent getting over jet lag, sleeping on an airbed in my friends’ uni halls and eating cheese toasties. Straight away after that I had sorted out a flat and a job in an Italian restaurant, impressing them with a few rusty Italian phrases; all I learnt from then on was pizza and swearwords.

During my gap year I partly lived and worked in Australia, so knew I was capable of marching into places with my CV and persevering until they felt bad and gave me a job. But this year abroad has shown me I can moved to a different country and create a life for myself, which I like to think is a pretty good skill.

Throughout the year I worked in three hectic restaurants, ran of a champagne bar at a Blues festival, and worked at another. I made a lot, spent A LOT, and saved to go travelling in Indonesia. I also shared a room the whole time with a variety of people, including an American girl who ate curry in bed and could make bongs out of apples. At one point we had eight people staying in our tiny two-bedroom flat, which I guess taught me the skills of tolerance and washing up.

At Warwick I study History of Art with a bit of Italian, but at Monash I wanted to study a wider range of practical things I was interested in and thought would help me get the sort of job I want. I chose photography, sustainable societies, world religions, travel writing and journalism. All were great and gave me a more rounded education in things I really enjoy. I also found that all were taught by passionate, proactive leaders in their fields who encouraged us to be so too.

Amongst other stories, I created my own radio news story on an anti-abortion rally, and filmed and presented a TV story of the Melbourne World Naked Bike Ride. All in all I’d say my year down under has hopefully given me a few skills to get amongst the graduate job market, just TV presenting probably isn’t one of them.

Scarlett Mansfield

Over the course of my travels, I believe that I have gained valuable skills from the people I have met, and those skills will make me more employable. In terms of personal development, an incredibly valuable skill gained from travelling is an ability to think for yourself and solve problems. Being stranded in the middle of nowhere with no transport and no money pushes you to find an effective solution quickly!

Travelling also provides you with instances that show that you are willing to jump into the deep end and try new experiences. While in the Philippines, I agreed to go home to meet a man’s family who owned a company and preached the importance of reliability, dedication and hard-work on the road to success. It was a valuable experience and I couldn’t agree with them more. In employment these are the three main objectives that I strive for.

Another way in which travelling made me more employable is indirect. Travelling has emphasised to me the value of education. I, like many students, take for granted the access to education we have in the United Kingdom. After having seen people walking miles to school, and those too poor to make it, I realised that we ought to take full advantage of every opportunity we are given and thus push myself to work harder and achieve the higher grades employers seek.

Solene Van Der Wielen

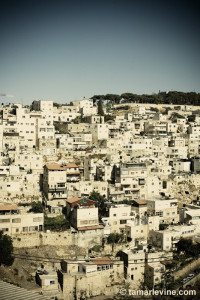

In need of a breath of fresh air before diving into my History degree, I used my time out of education to travel to a land where every square foot is an archaeological dig waiting to happen: Israel.

After wading through websites and newsletters, I found myself working in a hostel/hotel/interfaith dialogue peace project in the center of Nazareth’s old town. In a renovated Ottoman mansion, I learned to man the reception, bake cakes with odd ingredients, foam milk for coffee, but most of all how to interact with and assist complete strangers.

The enclosed courtyard of the hostel meant that, after a long day of visiting natural and religious wonders, travellers could retire to our little bubble and expect calm, company, and cake. Having already initiated conversation with clients upon their arrival and provided a detailed map of the area, it became easier to genuinely interact with them and to tailor information that could improve not only their stay but the rest of the trip.

I discovered purpose where I’d never expect it, both in the social enterprise (returning life to the once decrepit old town and promoting interaction between local Jews, Christians, and Muslims) and in the mundane activities that running a hostel requires.

I became genuinely eager to help, be it through using my languages or helping staff set out breakfast. Visitors were interested in what we did with our time, giving tours of the old town, helping the local community gain confidence and expand, and we could share all that by just remaining open to their questions and open-minded generally.

I came away with a different vision of work, people, and possibilities, one that has served me well since and no doubt will continue to do so in the upcoming years.’

Michael Perry

In the summer of 2010, I was feeling pretty petrified as I faced down an unplanned gap year. My (apparently shaky) UCAS application had secured me no university offers, meaning I had to re-apply for 2011, despite the fact that I had already bagged the grades I was after.

At the time, I naturally saw my situation as far from ideal. In hindsight, however, an impromptu year out of education was one of the best things to happen to me. After spending the first few months raising money by working six-day weeks in a local café, I had enough savings to fund a long summer of adventuring, satisfying my burgeoning wanderlust with stints in New York and around several Caribbean islands.

Best of all, I was free to pack my rucksack and spend a month hopscotching around Europe, building friendships with nomadic strangers as we absorbed everything from Swiss mountaintops to the spires of Prague and bar crawls in deepest Berlin. I even got to shatter my fear of heights by taking a huge personal leap and paragliding over the alps of Austria.

After returning home to quiet, quaint southern England, my funds were mostly depleted, and there was no time left over to do anything but prepare myself for three years at university. I finished my gap year having secured no promotions, no major charitable accomplishments, and no new business connections. But I’m totally fine with that.

While I can’t pinpoint much about my gap year that I’d readily squeeze onto my CV, I feel incredibly grateful having had the opportunity to grow as a person, beyond the pressure of the academic calendar. Personally, I believe that whatever we do with our time off – from a couple of weeks to an entire year – it’s got to mean something to us, even if only in a subjective context. If what we do is not strictly useful in a professional sense, as long as it’s personally stimulating (whether that’s making memories, building confidence, or acquiring new hobbies and proficiencies), it can be of equal benefit.

In my case, I came to Warwick with a greater measure of independence, a much stronger sense of confidence and self-esteem, several journals’ worth of anecdotes, and the knowledge that I made something from nothing in a year of minimal prospects.

Comments