Chick lit in the twenty-first century

[dropcap]E[/dropcap]verybody has a guilty pleasure when it comes to reading. For some, it’s fantasy novels, comic strips, or even the likes of Fifty Shades of Grey. For me, it’s the generic chick lit novel: girl is lonely, girl meets unlikely match of a boy, girl and boy fall in love and live happily ever after (surprise, surprise). The simple and near-identical structure of these novels means I can remain right in the centre of my literary comfort zone. However, recently it’s come to my attention that chick-lit isn’t quite as superficial as it first appears to be.

A few years ago, a large proportion of this genre of literature was centred on female body image. Obesity was a hot topic in the UK and USA, as shocking statistics were being poured out over the media concerning the 61% of the population deemed to be within this category (statistics as of the NHS’ report concerning obesity in 2010). At this time, and for a couple of years preceding it, chick lit authors positioned this issue at the forefront of their novels. This encouraged people, especially young women, to love their bodies even if they are technically overweight.

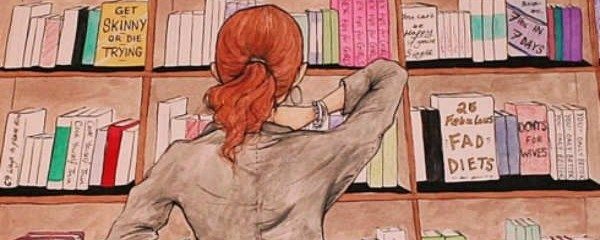

[pullquote style=”left” quote=”dark”]Chick-lits fights against the endless ‘fat-shaming’ in the media[/pullquote] This body-beautiful campaign as such was taken up by many authors worldwide, including one of my personal favourites, Meg Cabot (Princess Diaries anyone?). Her range of adult novels includes the Heather Wells mystery series, which tracks the progress of a young woman who has been criticised because of her large size. The books explore the idea that being overweight does not make a person unattractive, or unsuccessful. Thus, they fight against the endless “fat shaming” in the media: critiques of celebrities gaining a few pounds and the endless avocation of (unhealthy) fad diets in almost every female-targeted magazine.

Recently however, as the issue of obesity has become a less pressing issue in the media, chick lit authors have turned their attention elsewhere. Recent figures in mental health statistics have becoming increasingly alarming: one in every four people experiences some form of mental health issue every year (the most common being depression and anxiety disorders). Again, as the media has begun to focus on these issues, so have chick lit authors. The two novels which I have read so far this summer as part of this genre have adhered to this. Both feature mentally unstable female protagonists who have undergone some form of trauma in their lives and thus (unfortunately) need to be rescued by the loving, handsome boy-next-door.

After a hectic period of second year English Lit exams and getting a new kindle for my birthday I really wanted to chill out with a simple chick-flick on holiday. As a student I obviously instantly started scrolling through the reams of (largely awful-looking) free books in this style on Amazon. Coming across Denise Grover Swank’s Twenty Eight-and-a-Half Wishes I didn’t expect much, and the opening chapters held out to this expectation.

The book is set in a modern Southern style landscape. The protagonist is an anxious 24-year-old girl who finds it hard to feel appropriate emotions towards events. She lost her father at a young age and is controlled by a wicked mother. This Cinderella-esque storyline was waiting for a Prince Charming to arrive, but, akin to most other romantic novels of our era, Joe McAllister is a rugged, mysterious figure. This generic outset initially jars with the magic realism that Rose’s visions imbibe the plot with. Her blunt reaction to (not giving any spoilers) certain tragic incidents in the novel heightens this; in my opinion making this protagonist and the book itself too unrealistic.

The book is set in a modern Southern style landscape. The protagonist is an anxious 24-year-old girl who finds it hard to feel appropriate emotions towards events. She lost her father at a young age and is controlled by a wicked mother. This Cinderella-esque storyline was waiting for a Prince Charming to arrive, but, akin to most other romantic novels of our era, Joe McAllister is a rugged, mysterious figure. This generic outset initially jars with the magic realism that Rose’s visions imbibe the plot with. Her blunt reaction to (not giving any spoilers) certain tragic incidents in the novel heightens this; in my opinion making this protagonist and the book itself too unrealistic.

However, after the disappointment of these first few chapters the novel improves greatly. It develops into a mystery-romance novel rather than a mere romance one, which offers much more to the reader in terms of plot and interest. Moreover, Rose’s visions no longer seem to jar with the main plot, but cohere with and enhance it, allowing the reader as well as Rose to have a stronger grasp of the mystery at hand than most other characters in the text. Rose’s visions as well as her social anxiety arguably hint at deeper mental issues within her character. However, the fact that the visions save Rose’s life portrays an important message to the reader: mental illnesses do not have to destroy your life. This is something which Rose learns as she develops as a character.

Similarly, Natasha Preston’s first book in her (appropriately named) Silence series raises a great number of important issues surrounding the moving issue of childhood sexual abuse. Despite a pretty good (albeit clichéd) romantic back story to the plot, the traumatic effects of this type of abuse upon a teenage girl remained the key focus of the novel. Silence follows the story of 15-year-old Oakley who hasn’t uttered a single syllable since the age of 5. Her overwhelming love for her 17-year-old best friend/neighbour/all-round good guy Cole encourages her to consider the impact of her silence on others, including her family: Oakley, her loving parents and sex-obsessed older brother. But as the novel rapidly makes clear, Oakley’s silence isn’t the only aspect of the family’s problems which doesn’t immediately meet the eye …

Set in England, the social issues which this novel raises really struck home for me. Moreover, with the recent numerous allegations of child sexual abuse by famous men in the media business, the concerns this novel raises are at the heart of heated discussions in the UK: can we really trust our children with anyone? How does this kind of abuse affect the mental health of the victim as they reach puberty and beyond?

Set in England, the social issues which this novel raises really struck home for me. Moreover, with the recent numerous allegations of child sexual abuse by famous men in the media business, the concerns this novel raises are at the heart of heated discussions in the UK: can we really trust our children with anyone? How does this kind of abuse affect the mental health of the victim as they reach puberty and beyond?

I believe that the most important aspect of this novel is the exploration of the ways in which sexual predators transform their victims in order to cover up their horrendous acts against human decency. Oakley has her voice physically and metaphorically removed in a hyperbolic symbolization of the fear in which these victims live.

Once you get past the slightly bad writing that characterises the initial chapters of both the books discussed above, they really do expose some harsh realities about the state of modern life. Women are statistically more likely to suffer from depression than men, which perhaps explains why these authors have chosen to portray their female protagonists as fragile and imperfect. Perhaps they want to suggest that if you really get to know a person (as the reader does with the narrative voice) everyone is broken. However, there may be a greater issue at hand: are these modern chick lit authors falling into the fallacy of creating almost 19th century female protagonists who can’t survive without swooning into the arms of a life-giving, life-saving man?

[divider]

Comments